Section 1

Michael FliriBio

The photographs in My Private Fog II present a performance by Michael Fliri.

The artist wears a number of transparent masks created out of a mould of stones and minerals

gathered on his hikes in the high mountains. Initially separate entities, the two bodies

gradually merge like inhabitants of the same atmospheric space.

The condensation generated by the breath gradually causes the artist’s face to disappear. It

transforms the surfaces into images reminiscent of snow-clad mountain silhouettes, glaciers or

rocky matter, underscoring the biological interaction between human being and nature. By making

visible what our eye tends not to see, Michael Fliri opens up a space of reflection on the

concepts of interaction and metamorphosis.

Bringing to mind late-19th-century research conducted by the physiologist Angelo Mosso on the

action of mountain air on the human body, the images make manifest the constant process of

exchange with the extra corporeal environment to which every human being is subject.

Michael Fliri

My Private Fog II, 2017

Photographs

Courtesy of the artist and Raffaella Cortese Gallery, Milan

Photos: Rafael Kroetz

Snow and Glaciers: Forms, Functions and Vulnerability

Experiences conducted in central and northern Europe have surprisingly demonstrated how

forest immersion in winter, in an environment with a layer of snow and ice on the

ground, can produce significant benefits for mental health, comparable with experiences

conducted in the spring and summer periods.1 A view of snow

and ice, with their relative repetitive structures – from great snow-covered expanses to

the tiniest ice crystal, the true prototype of the “fractal” form – is the most relaxing

thing and the least demanding of our attention. So, snow-covered winter environments

provide direct ecosystemic services for human health, and these are but the tip of the

iceberg of the services rendered by snowy and glacial environments.

In fact, snow cover and mountain and arctic glaciers render the fundamental ecosystemic

service of gradually releasing rainwater, preventing disastrous floods and ensuring a

relatively constant supply of water throughout the year to fulfil the demands of

irrigation, drinking water and hydroelectric energy generation. In the high-mountain

environment and at other high latitudes, the ice that remains all year round in the

subsoil – permafrost – ensures the stability of the slopes and the ground itself,

preventing instability and guaranteeing the stability of buildings.2

These natural elements are, however, subject to imminent danger: snow, ice and the

glaciers are truly among the elements most sensitive to climate change. Snowfall is

increasingly irregular, rises ever higher and the thawing cycle is ever more rapid,

undermining the sustainability of ski resorts and accelerating the water cycle.3 As well as economic and territorial consequences, the

presence and persistence of snow or ice has always represented the passing of the

seasons and, more in the long term, changes to the high-mountain landscape. The swift

retreat and increasingly marked loss of both the snow and entire glacier systems, with

processes now measured in terms of the decade if not a few years, is a source of anxiety

and stress for mountain residents and for all high-mountain lovers and visitors who have

often been frequenting them for their entire lives.

The alpine glaciers have lost 70% of their volume in just over a century, making way for

scree, landslides and risks for mountaineers.4 Following

catastrophic collapse, the glaciers of Greenland and west Antarctica are threatening to

flood coastlines worldwide.5, 6 The expanse of Arctic sea

ice, perhaps the most obvious indicator of climate change, has more than halved in

summer over the last 40 years, in a spiral that, in still uncertain times, might lead to

a remodelling of all the Great Northern landscape with fatal consequences for fauna and

local populations, and perhaps destined to generate a terrible new scenario of conquest

and war.7

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- A. Peterfalvi, M. Meggyes, L. Makszin, N. Farkas, E. Miko, A. Miseta, L. Szereday, “Forest bathing always makes sense: Blood pressure-lowering and immune system-balancing effects in late spring and winter in central europe”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2021, 1–20. LINK→

- E. E. Webb, A. K. Liljedahl, J. A. Cordeiro, M. M. Loranty, C. Witharana, J. W. Lichstein, “Permafrost thaw drives surface water decline across lake-rich regions of the Arctic”, Nature Climate Change, 12(9), 2022, pp. 841–846. LINK→

- H. François, R. Samacoïts, D. N. Bird, J. Köberl, F. Prettenthaler, S. Morin, “Climate change exacerbates snow-water-energy challenges for European ski tourism”, Nature Climate Change, 13(9), 2023, pp. 935–942. LINK→

- M. Carrer, R. Dibona, A. L.Prendin, M.Brunetti, “Recent waning snowpack in the Alps is unprecedented in the last six centuries”. Nature Climate Change, 13(2), 2023, pp. 155–160. LINK→

- L. J. Larocca, M. Twining–Ward, Y. Axford, A. D. Schweinsberg, S. H. Larsen, A. Westergaard–Nielsen, G. Luetzenburg, J. P. Briner, K. K. Kjeldsen, A. A. Bjørk, “Greenland-wide accelerated retreat of peripheral glaciers in the twenty-first century”, Nature Climate Change, 13(12), 2023, pp. 1324–1328. LINK→

- K. A. Naughten, P. R. Holland, J. De Rydt, “Unavoidable future increase in West Antarctic ice-shelf melting over the twenty-first century”, Nature Climate Change, 13(11), 2023, pp. 1222–1228. LINK→

- D. Topál, Q. Ding, “Atmospheric circulation-constrained model sensitivity recalibrates Arctic climate projections”, Nature Climate Change, 13(7), 2023, pp. 710–718. LINK→

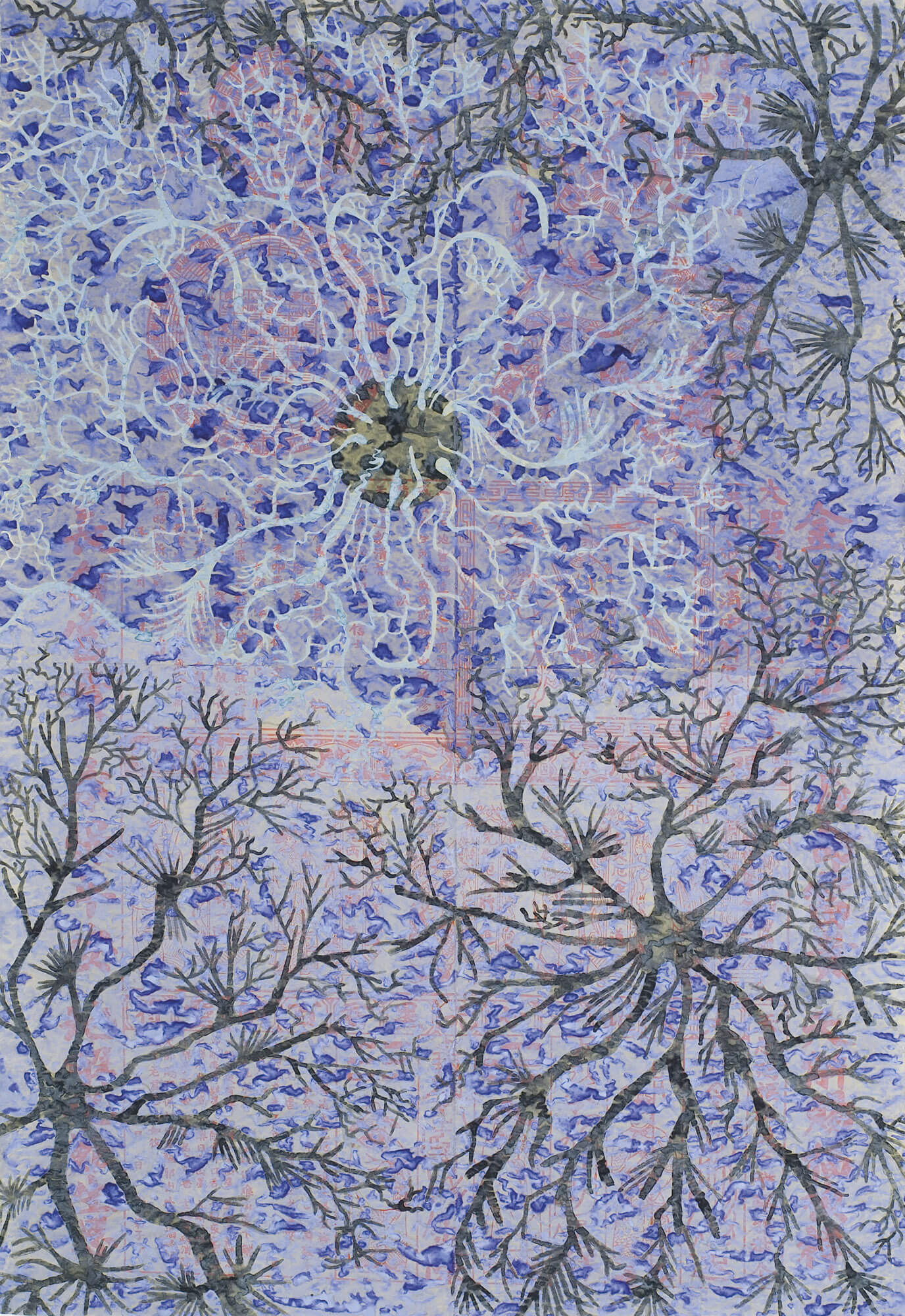

Alberto Di FabioBio

Born in 1966 in Avezzano, in the province of L’Aquila, with an artist father and a

natural-science teacher mother, Alberto Di Fabio has always been deeply bound to the land of his

origins. The high uplands of Marsica in the Abruzzi in Central Italy formed the background for

his entire childhood; they were the subjects of his earliest drawings and certainly the primary

source of inspiration for an artistic output that has constantly evolved over time.

From these beginnings, mountains – what the artist would call a “goddess, almost a divinity” –

would be constantly depicted, first through canvases and works on paper, then through

environmental wall paintings.

Since his early works, Di Fabio has been inspired by the world of natural sciences including

biology, chemistry and astronomy. His painting explores atoms, cell structures, neurons, DNA

chains, constellations and galaxies in a constant attempt to decipher the laws of the universe

and depict the invisible processes that govern relations between the living and non-living

worlds.

The large wall painting entitled Materia invisibile encapsulates all the sensations

experienced

by the artist on one of his first encounters with the mountain environment: the energy emanated

by light, the smell of falling rain, the allure of the surrounding landscape and that of the

blue, azure, grey and white sky above him. With a gestural and performance painting centred on

extremely physical and emotional participation and the use of his own optical and mental

microscope, Alberto Di Fabio accompanies onlookers on a journey through the mystery of matter,

through the forms and consistencies of the heterogeneous, molecular and subatomic structure of

nature.

Seeing Nature

The sense of well-being and relaxation experienced before natural landscapes compared

with man-made ones is already established and documented.

The first explanation stems from the fact that human beings respond in a far simpler and

more immediate manner to stimuli present in the natural environment than in artificial

ones – that is, with more “fluid perception” (the ease with which a stimulus is

processed by the brain).1-2

For example, processing visual stimuli connected to natural environments requires less

effort of us than to artificial ones, as demonstrated by several studies analysing the

activation of different parts of the brain and eye movement according to the stimuli

presented to us.2

Somehow, it is as if we were “programmed” to easily process the stimuli present in the

natural environment, which has been our habitat for the greater part of human history.

This is why certain features of natural environments, from geometric forms to the

variability of sunlight and the soundscape, demand low levels of attention and cognitive

load.

Several studies in the neuroscience field have, for instance, shown that people prefer

so-called “fractal” shapes, that is repetitive and recursive ones. These structures are

typical and frequent in natural environments as opposed to anthropomorphic ones.3-4 Forests, just like every single tree, are quintessential

examples of fractal geometric structures. They are composed of similar structures which

are repeated on different, ever smaller, spatial scales: the branches of a tree look

like small versions of the tree itself and this applies down to the twigs and tiniest

ramifications.

Visualising repetitive scenes encourages relaxation and therefore reduces the activity

of the sympathetic system, particularly “hyperactive” in patients suffering from

depression and anxiety, producing genuine therapeutic effects in these subjects but also

in so-called “healthy” individuals in general.5

As well as the presence of repetitive structures (trees, forests), the mountain

environment can also be a place of well-being merely because it is generally located far

away from man-made infrastructures: well-being prompted by silence, punctuated by the

relaxing sounds of the forest, as too by the quality of the night sky. In fact, darkness

– in Italy found now only on a few remote islands and the most isolated mountain

scenarios – translates into an opportunity to reconnect with an essential component of

natural well-being. And yet, more than 70% of the world’s population has never seen the

Milky Way: vegetation, fauna and humans themselves are subjected to constant and

potentially harmful stress because of the poor quality of nocturnal darkness.6

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- S. Kaplan, “The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 1995, 169–182.

- A. E. van den Berg, Y. Joye, S. L. Koole,“Why viewing nature is more fascinating and restorative than Koole, viewing buildings: A closer look at perceived complexity”, Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 20, 2016, pp. 397–401. LINK→

- Y. Joye, A. van den Berg “Is love for green in our genes? A critical analysis of evolutionary assumptions in restorative environments research”, Urban For Urban. Greening, 10, 2011, pp. 261–268. LINK→

- C. M. Hagerhall, T. Laike, R. P. Taylor, M. Küller, R. Küller, T. P. Martin, “Investigations of human EEG response to viewing fractal patterns”, Perception, 37(10), 2008, pp. 1488–1494. LINK→

- Song, Chorong, et al., “Physiological Effects of Visual Stimulation with Forest Imagery”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 2018. LINK→

- E. Mazzoleni, M. Vinceti, S. Costanzini, C. Garuti, G. Adani, G. Vinceti, G. Zamboni, M. Tondelli, C. Galli, S. Salemme, S. Teggi, A. Chiari, T. Filippini, “Outdoor artificial light at night and risk of early-onset dementia: A case-control study in the Modena population, Northern Italy”. Heliyon, 9(7), 2023 , e17837. LINK→

Andrea NacciarritiBio

Stipa tenuissima plants contained in a piece of turf are moved by the air generated by a

fan.

Andrea Nacciarriti has reconstructed a portion of a field swept by an artificially created gust

of wind. In doing so, he has recreated a natural mechanism and brought what habitually happens

outdoors indoors.

The work stems from the artist’s desire to visualise the air, a typically invisible element

which only becomes perceptible via the effects it produces when it becomes wind and the pressure

of its molecules encounters matter.

With this work, Nacciarriti invites us to consider the role and impact that the non-visible part

of nature exercises on us. The artist urges our gaze to go beyond the threshold of the visible.

As is often the case in his practice, it is through the power of synthesis that the artist is

able to propose representations of great conceptual, symbolic and aesthetic power.

Air as Eros and Thanatos

Despite Aristotle’s ancient intuition, the fact that air has mass and so can exercise

pressure was only fully understood 500 years ago by Galileo Galilei and Evangelista

Torricelli. Continuously powered by the sun, wind and pressure play an endless

two-handed game, with pressure gradients creating wind and wind equalising differences

in pressure. At all scales, wind is determined by the atmospheric pressure gradient, as

well as by the Coriolis force resulting from the Earth’s rotation. In their turn,

pressure gradients form in response to differences in heating, usually inherent in

different insolation, both at ground level and along the atmospheric column. Thanks to

the research of the Russian physicists Anastassia Makarieva and Victor Gorshkov, since

the end of the 2000s, it has been posited – and then widely confirmed – that the great

natural forests, both tropical and boreal, generate far-reaching pressure gradients

through the transpiration of water vapour and subsequent condensation and immense heat

release. In this way, the great forests – but only natural, balanced ones – are capable

of “recycling” the masses of moist ocean air, transporting it for thousands of

kilometres and thus bringing rain to areas that would otherwise be semi-deserts.1, 2 This is the so-called “biotic pump” that generates

rainfall and therefore networks of life.

Air is like Eros and Thanatos. Oxygen gives life, enabling cellular respiration, and, at

the same time, oxidises and destructs our cells. Other compounds in the air are,

instead, a direct consequence of our lifestyle: rich in either pollutants or in

beneficial compounds, certain terpenes – components of essential oils – in particular

among the latter, are emitted by the trees and ground of forests, as confirmed by

consolidated scientific evidence. Over the long period in history when humans inhabited

the forest, our organism adapted to best exploit the properties of the forest

atmosphere. That is why whenever we immerse ourselves in the forest, certain terpenes

become significant vehicles of mental (anxiolytic, sedative) and physiological

(antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and activating immune defences)

well-being.3-5

On a global level, more than 90% of people breathe air that does not meet World Health

Organization (WHO) standards. As well as damage to the cardio-respiratory system, recent

scientific evidence points to a connection between some neurological issues and air

pollution, relative to both neurodevelopmental disorders in children and to

neurodegenerative diseases in adults.6

For example,

research conducted by a team of Mexican

scientists found changes in the structure of the brain, cognitive deficits and

pathologies similar to Alzheimer’s disease in a group of children in Mexico City – the

most polluted city in the world according to the United Nations – compared to children

who live in a less polluted city.7

Another study on almost three thousand schoolchildren in Barcelona found that cognitive

development was slower in students who attended schools with greater traffic

pollution.8

A growing number of studies supports the claim that greater exposure to atmospheric

pollution is associated with a decline in cognitive functions in adults or is, in any

case, a significant risk factor in cognitive decline and dementia in the elderly.9

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- A. M. Makarieva, A. V. Nefiodov, A. D. Nobre, M. Baudena, U. Bardi, D. Sheil, S. R. Saleska, R. D. Molina, A. Rammig, “The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence”, Global Change Biology, 29(9), 2023, pp. 2536–2556. LINK→

- E. Gies, “More than carbon sticks”, Nature Water, 1(10), 2023, pp. 820–823. LINK→

- M. Antonelli, D. Donelli, G. Barbieri, M. Valussi, V. Maggini, F. Firenzuoli, “Forest volatile organic compounds and their effects on human health: A state-of-the-art review”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 2020, pp. 1–36. LINK→

- D. Donelli, F. Meneguzzo, M. Antonelli, D. Ardissino, G. Niccoli, G. Gronchi, R. Baraldi, L. Neri, F. Zabini, “Effects of plant-emitted monoterpenes on anxiety symptoms: A propensity-matched observational cohort study”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2023, 2773. LINK→

- D. Donelli, M. Antonelli, R. Baraldi, A. Corli, F. Finelli, F. Gardini, G. Margheritini, F. Meneguzzo, L. Neri, D. Lazzeroni, D. Ardissino, G. Piacentini, F. Zabini, A. Cogo, “Exposure to Forest Air Monoterpenes with Pulmonary Function Tests in Adolescents with Asthma: A Cohort Study”, Forests, 14(10), 2012. LINK→

- P.J. Landrigan, “Air Pollution and Health”. The Lancet Public Health, 2(1), 2017, pp. 4–5. LINK→

- L. Calderón-Garcidueñas, R. Torres-Jardón, R.J. Kulesza, Y. Mansour, L. González-González, A. Gónzalez-Maciel, R. Reynoso-Robles, P.S. Mukherjee, “Alzheimer disease starts in childhood in polluted Metropolitan Mexico City. A major health crisis in progress”, Environmental Research, 183, 2020, 109137. LINK→

- P. Dadvand, J. Pujol, D. Macià, G. Martínez-Vilavella, L. Blanco-Hinojo, M. Mortamais, M. Alvarez-Pedrerol, R. Fenoll, M. Esnaola, A. Dalmau-Bueno, M. López-Vicente, X. Basagaña, M. Jerrett, M. J. Nieuwenhuijsen, J. Sunyer, “The Association between Lifelong Greenspace Exposure and 3-Dimensional Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Barcelona Schoolchildren”, Environmental Health Perspectives, 126(2), 2018, 027012. LINK→

- J. McLachlan, S.R. Cox, J. Pearce, M. Valdés Hernández, “Long-term exposure to air pollution and cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Frontiers in Environmental Health, 2, 2023. LINK→

Nona InescuBio

Using video, sculpture, photography and installations, Nona Inescu gives shape to studies centred

on redefining relations between the human and non-human body.

Adopting post-humanism as her preferred viewing mechanism, the artist forces physical and

conceptual visions with the aim of activating a speculative gaze.

Deep Breathing is a metal reproduction of a human rib cage, in which a series of

whitish colored

marine corals – in the phase of being formed can be seen.

The concepts of body, geological time and matter, reinterpreted on the basis of a new biological

awareness and a new cultural perspective, produce a porous aesthetic in which the contamination

between inside and outside, living and non living, human and other than human,

I and the other

is clearly evident.

Nona Inescu

Deep Breathing, 2019

Chrome steel, coral fragments

Collezione Katja Zigerlig, New York

Courtesy the artist and Catinca Tabacaru Gallery, Bucarest

Breathing in the Woods

Although generally an unconscious act, breathing forms the basis of our exchange with the

outside world: in fact, when we immerse ourselves in a wood, we inhale volatile

substances emitted into the forest atmosphere by vegetation and the ground.

Forest ecosystems release large quantities of these substances, called BVOCs (biogenic

volatile organic compounds).1 These are molecules, whether

heavy or light, formed of carbon and hydrogen; some also of oxygen. They fall under

several chemical classifications (more than 1700 compounds from a total of 90 families

of molecules have been identified to date) and have the common characteristic of being

volatile, to an extent also related to their molecular weight, so they can disperse in

the air.

Resulting from the secondary metabolism of plants, these compounds are a “language of

smells” that enables immobile plants to communicate with other plants, and above all to

ward off parasites and, on the contrary, to attract pollinator insects. The emission of

BVOCs increases when a plant is moderately stressed, in particular in response to an

attack from parasites.2

When inhaled, some of these substances, the low-molecular-weight light monoterpenes in

particular, easily overcome the blood-brain barrier and, thanks to their solubility in

blood, enter into circulation and reach all the organs, performing important “bioactive”

functions: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory and relaxing (anxiolytics,

sedatives and antidepressants) actions that are beneficial for cognitive processes. The

best known and most functional monoterpenes are a- and ß-pinene, ß-ocimene, d-limonene,

sabinene, myrcene and camphene. Their beneficial effects are evinced both locally, on

the respiratory tract,3 and systemically, via a calming and

anxiolytic action,4

dependent on the dose inhaled. A significant boost to the immune system has also been

postulated.5-8

The properties of these compounds – which make the forest a natural dispenser of

aromatherapy – therefore contribute decisively to the mental and physical well-being we

can gain from exposure to a natural forest environment.

The quantity and type of terpenes emitted by plants depends in the first place on the

type of species. Conifers emit the most efficacious monoterpenes; other broad-leaved

trees such as holm oak and beech are more productive but emit terpenes that are

relatively less functional for our health.

Climate conditions (temperature, radiation) and the vegetative phase of the plants

strongly influence emission in the atmosphere, making the season and also the time of

day fundamental factors in the modulation of concentrations of precious terpenes in the

air.9

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- F. Loreto, M. Dicke, J.P. Schnitzler, T.C. Turlings, “Plant Volatiles and the Environment”, Plant, Cell and Environment, 37 (8), 2014, pp. 1905– 08, LINK→.

- M. Valussi, M. Antonelli, “Forest Volatile Organic Compounds”. Scholarly Community Encyclopedia, 2020. LINK→

- D. Donelli, M. Antonelli, R. Baraldi, A. Corli, F. Finelli, F. Gardini, G. Margheritini, F. Meneguzzo, L. Neri, D. Lazzeroni, D. Ardissino, G. Piacentini, F. Zabini, A. Cogo, “Exposure to Forest Air Monoterpenes with Pulmonary Function Tests in Adolescents with Asthma: A Cohort Study”, Forests, 14(10), 2012. LINK→

- D. Donelli, F. Meneguzzo, M. Antonelli, D. Ardissino, G. Niccoli, G.Gronchi, R. Baraldi, L. Neri, F. Zabini, “Effects of Plant-Emitted Monoterpenes on Anxiety Symptoms: A Propensity-Matched Observational Cohort Study”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2023, 2773. LINK→

- M. Zorić, S. Kostić, N. Kladar, B. Božin, V. Vasić, M. Kebert, S. Orlović, “Phytochemical Screening of Volatile Organic Compounds in Three Common Coniferous Tree Species in Terms of Forest Ecosystem Services”. Forests, 12(7), 2021, 928. LINK→.

- T. Kim, B. Song, K. S. Cho, I.-S. Lee, “Therapeutic Potential of Volatile Terpenes and Terpenoids from Forests for Inflammatory Diseases”, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(6), 2020, 2187. LINK→

- Q. Li, A. Nakadai, H. Matsushima, Y. Miyazaki, A. Krensky, T. Kawada, K. Morimoto, “Phytoncides (wood essential oils) induce human natural killer cell activity”. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 28(2), 2006, pp. 319–333. LINK→

- M. Antonelli, D. Donelli, G. Barbieri, M. Valussi, V. Maggini, F. Firenzuoli, “Forest volatile organic compounds and their effects on human health: A state-of-the-art review”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 2020, pp. 1–36. LINK→

- F. Meneguzzo, L. Albanese, G. Bartolini, F. Zabini, “Temporal and spatial variability of volatile organic compounds in the forest atmosphere”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 2019, 4915. LINK→

Pillole di salute per l'emergenza

This video was conceived by psychologist and therapist Dr Francesco Becheri, a representative of

the Club Alpino Italiano (CAI) Commissione Centrale Medica /

Comitato Scientifico Centrale, founder and scientific director of the Pian dei Termini forest therapy development and research project.

Born out of collaboration with Prof. Qing Li, immunologist, founder and chairman of the Japanese

Society of Forest Medicine and vice president of the International Society of Nature and Forest

Medicine; the Commissione Centrale Medica of CAI; the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR)

and the University of Florence, the video presents images of a number of scrupulously selected

woods and forests and the natural sounds recorded therein.

Shown to a sample of people imprisoned in their homes during the lockdown period, this video was

the focus of research conducted by those mentioned above to study the effects that viewing such

scenarios produced on levels of confinement anxiety.

The experiment lasted five days and was conducted remotely. The study was conducted in

collaboration with CNR (IBE and IFC) and Neurofarba – Department of Neuroscience, Psychology,

Drug Research and Child Health of the University of Florence. It demonstrated that the subject

group shown the video of the forests had a significantly greater reduction in anxiety activation

than the control group, exposed to a video of urban contexts.

From a Feeling to a Science

Effects of Forest Bathing on Human Health

Researchers in Japan have tried to find a new method to reduce stress by visiting forests

and have proposed a new concept called “Shinrin-Yoku or Forest Bathing” in 1982.

Shinrin in Japanese means ‘forest’, and yoku means ‘bath’. So

shinrin-yoku means bathing

in the forest atmosphere, or taking in the forest through our senses. This is not

exercise, or hiking, or jogging. It is simply being in nature, connecting with it

through our sense of sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch.

Shinrin-Yoku is like a bridge. By opening our senses, it bridges the gap between us and

the natural world.

In Japan, since 2004, serial tudies have been conducted to investigate the effects of

this practice on human health. We have established a new medical science called Forest

Medicine.

The Forest Medicine is a new interdisciplinary science, belonging to the categories of

alternative medicine, environmental medicine and preventive medicine, which studies the

effects of forest environments (Forest Bathing/Shinrin-Yoku/Forest Therapy) on human

health. In 2007 we established the Japanese Society of Forest Medicine.

It has been scientifically reported1 that Forest

Bathing/Shinrin-Yoku (forest therapy) has the following beneficial effects on human

health:

1. Boosts immune function by increasing human natural killer (NK) activity, the number

of NK cells, and the intracellular levels of anti-cancer proteins, suggesting a

preventive effect on cancers.

2. Reduces stress hormones, such as urinary adrenaline and noradrenaline and

salivary/serum cortisol contributing to stress management.

3. Improves sleep.

4. Shows preventive effect on depression by improving positive feelings and serotonin in

serum and reducing negative emotions.

5. Reduces blood pressure and heart rate showing preventive effect on hypertension.

6. May apply to rehabilitation medicine.

7. In city parks also has benefits on human health.

8. Has preventive effect on lifestyle related diseases by reducing stress.

9. Shows preventive effect on COVID-19 by reducing stress and boosting immune

function.2

10. Phytoncides3 play an important role in Shinrin-Yoku.

— Qing Li, MD, PhD

Professor at Nippon Medical School, Tokyo

Vice-president and Secretary General of the International Society of Nature and Forest

Medicine (INFOM)

President of the Japanese Society of Forest Medicine

- V. Roviello, M. Gilhen-Baker, C . Vicidomini, G.N. Roviello, “Forest- bathing and physical activity as weapons against COVID-19: a review”, Environ Chem Lett, 131-140. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01321-9.

- V. Roviello, M. Gilhen-Baker, C. Vicidomini, G.N. Roviello, "Forestbathing and physical activity as weapons against COVID-19: a review", Environ Chem Lett, 131-140. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01321-9.

- Phytoncides are the natural oils within a plant and are part of a tree’s defence system. Trees release phytoncides to protect them from bacteria, insects and fungi. Phyton is Latin for ‘plant’, and cide is ‘to kill’. Phytoncides are also part of the communication pathway between trees: the way trees talk to each other. The concentration of phytoncides in the air depends on the temperature and other changes that take place throughout the year. The warmer it is, the more phytoncides there are in the air. The concentration of phytoncides is at its highest at temperatures of around 30 degrees Celsius.

.jpg)