Section 3

Christian FogarolliBio

In his research, characterised by a multidisciplinary approach, Christian Fogarolli frequently

draws on research and knowledge that come from the worlds of psychology, medicine and archiving,

as well as art. Always interested in exploring mental, social and cultural dynamics at the base

of humankind’s thinking and acting, Fogarolli has realised the work PillPlant, in which

human

and non-human are presented as parts of the same body.

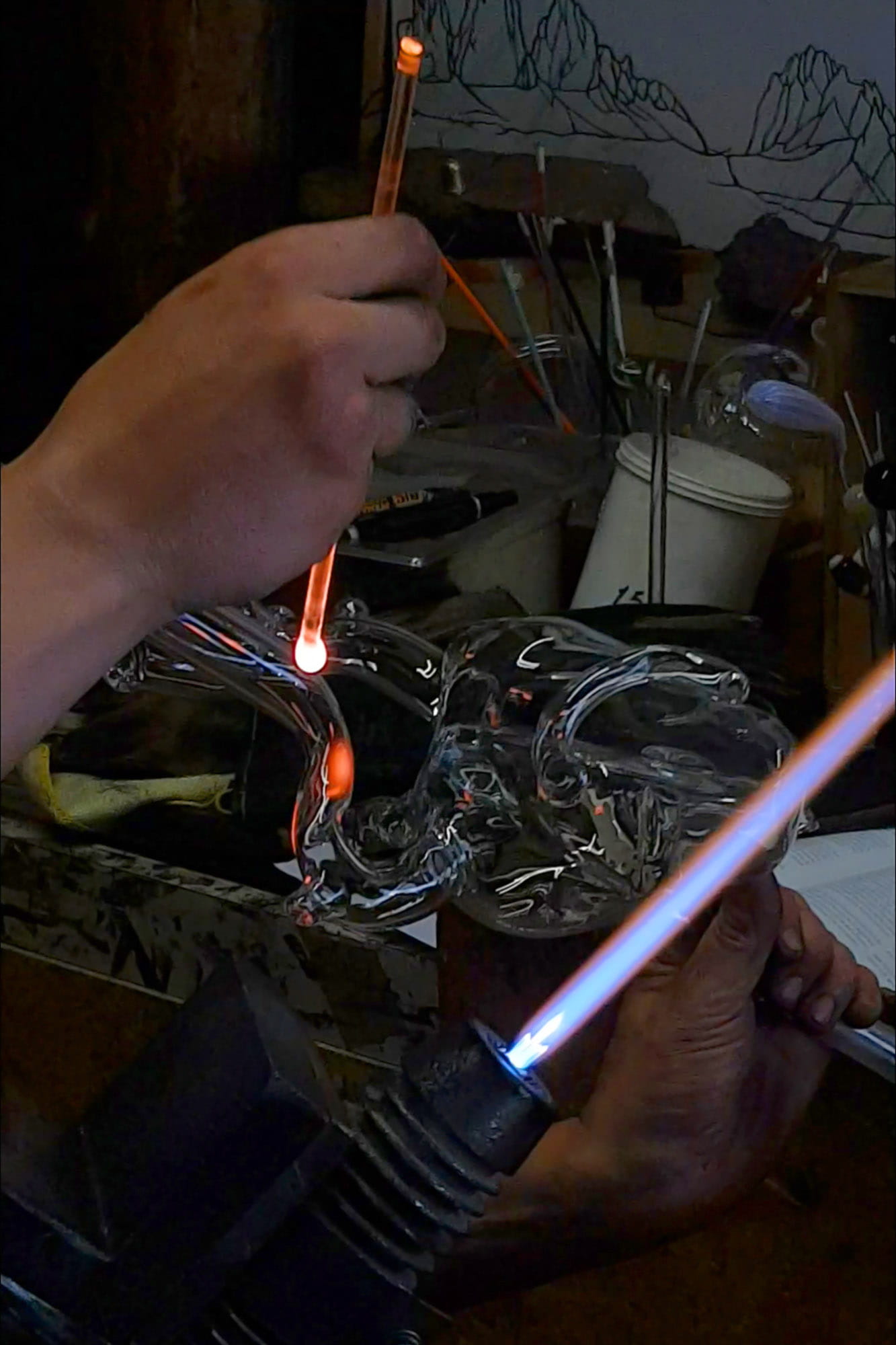

His blown-glass sculptures, which reproduce human organs, limbs and body parts, accommodate

within themselves plants and natural elements of proven therapeutic efficacy.

In fact, recent studies show that contact with natural environments, such as green areas, woods

and forests, results in less incidences of allergy, autoimmune disturbances and high stress

levels and, conversely, an improvement in cardiovascular functions, and in hemodynamic,

neuroendocrinic, metabolic and oxidative indices, as well as in mental processes and psychic

well-being. In these natural or mountainous environments, medicinal herbs and plants are

present: natural products endowed with specific active ingredients that vary in nature:

anti-inflammatory, sedative, tonifying, purifying.

Their use dates way back. In ancient Greece they were the only remedy for treating disorders and

illnesses while, in the late 1700, with the advent of phytotherapy and homeopathy, the

therapeutical importance of these plants was studied. It is also most likely that primitive

Ötzi, in the throes of abdominal pain, consumed ferns in an attempt at self-medication.

Christian Fogarolli

PillPlant, 2024

Blown-glass sculptures, mountain medicinal plants, liquids and various materials

Different dimensions

Plants and extracts provided thanks to the collaboration of NIRIS LAB, Polo Meccatronica,

Rovereto

Courtesy the artist and Alberta Pane Gallery, Paris-Venezia

Mountain Biodiversity

The extreme environmental conditions that typify the mountain environment represent a

great challenge for the organisms that live there. The interaction between climate and

mountains produces an extremely complex environmental heterogeneity that leads to a

greater diversity of species that succeed in adapting to local conditions. The habitat’s

ecological variety, even over short altitude differences, as well as geographic

isolation, means that mountains are important centres of diversification and hotspots of

biodiversity.1

In fact, mountains are home to about a third of the diversity of terrestrial species and

include 30% of the so-called key areas for biodiversity: areas that significantly

contribute to the global persistence of biodiversity and priority regions for

conservation.

Stress forces plants to equip themselves in order to survive adverse conditions. Marked

temperature variations, lower oxygen availability, strong winds, low temperatures and

high solar radiation are all factors that lead to the production of free radicals and

other molecules that are hazardous for cellular structures.

To protect themselves from free radicals, mountain plants produce large quantities of

antioxidant compounds that are capable of reducing the damage caused by them to cells

and vegetal tissue.

This is why concentrations of antioxidant compounds in high-altitude flora are often

greater compared to concentrations in hill or plain plants.2

Only plants of arid, semi-desert agriculture – from pomegranate trees, to almonds to

prickly pears – can compete with the properties of mountain trees. For example, chestnut

wood provides the most antioxidant extracts, followed by the peel of the pomegranate

fruit, and then spruce bark and silver fir twigs.

These remarkable antioxidant properties are highly beneficial for human health, and,

indeed, many mountain plants have high medicinal properties that have been used for

millennia by populations even far from each other, as explained by research scientist

Adrienne Mayor of Stanford University.3 Today, research is

rediscovering these properties and their wider availability, thanks to new extraction

and standardisation technologies. Products extracted from mountain plants can make a

significant contribution towards protecting and controlling some of the focal points of

human health, among which metabolic equilibrium, cardiovascular health,

microcirculation, protection from free radicals, cancer prevention and even male and

female libido.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- C. Körner, “Mountain biodiversity, its causes and function: an overview”. Mountain Biodiversity, 2019, pp. 3-20.

- A. M. Hashim, B. M. Alharbi, A. M. Abdulmajeed, A. Elkelish, W. N. Hozzein, H. M. Hassan, “Oxidative Stress Responses of Some Endemic Plants to High Altitudes by Intensifying Antioxidants and Secondary Metabolites Content”, Plants, 9, 2020. LINK→

- A. Mayor, “Animals self-medicate with plants − behavior people have observed and emulated for millennia”, The Conversation, 2024. LINK→

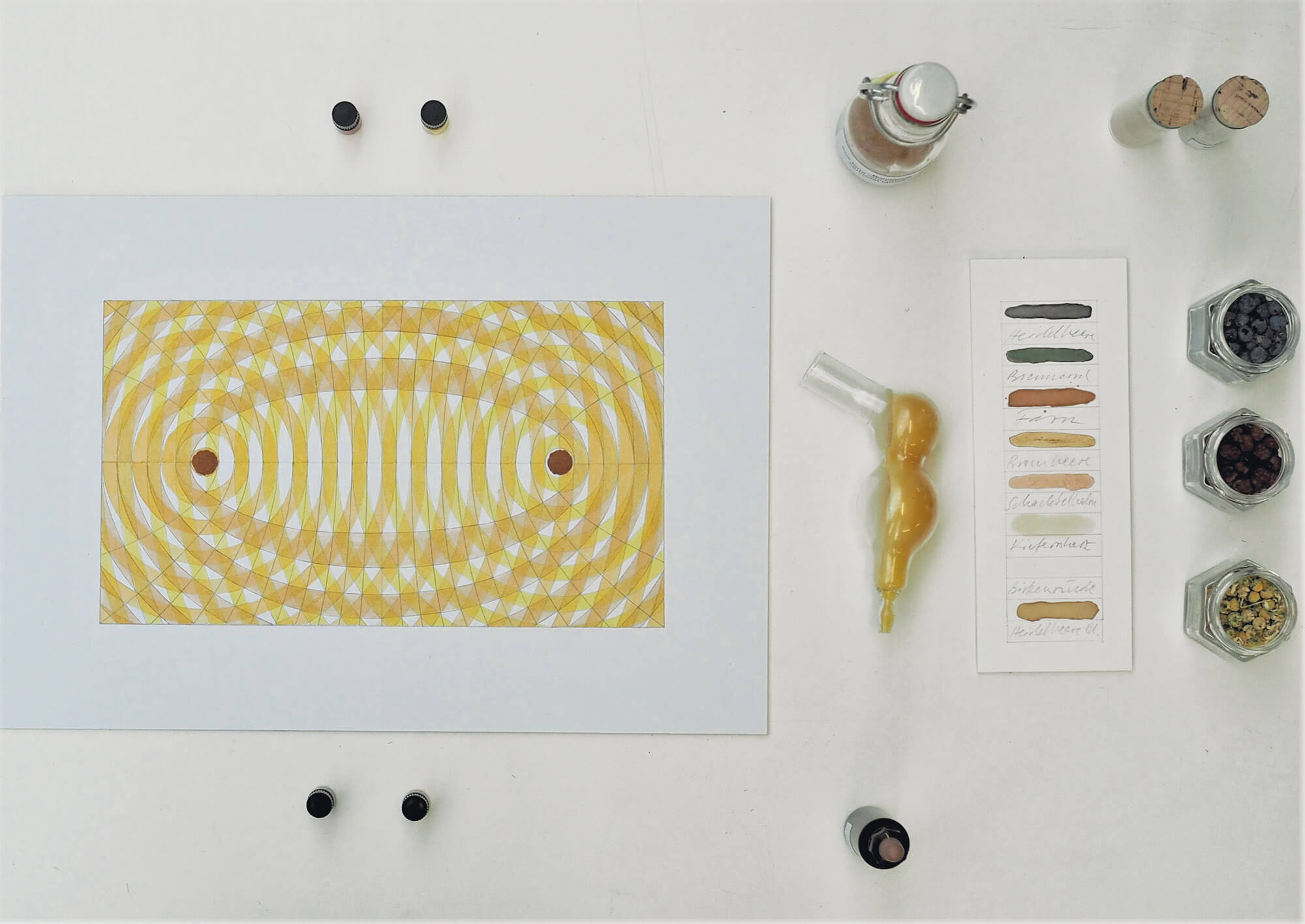

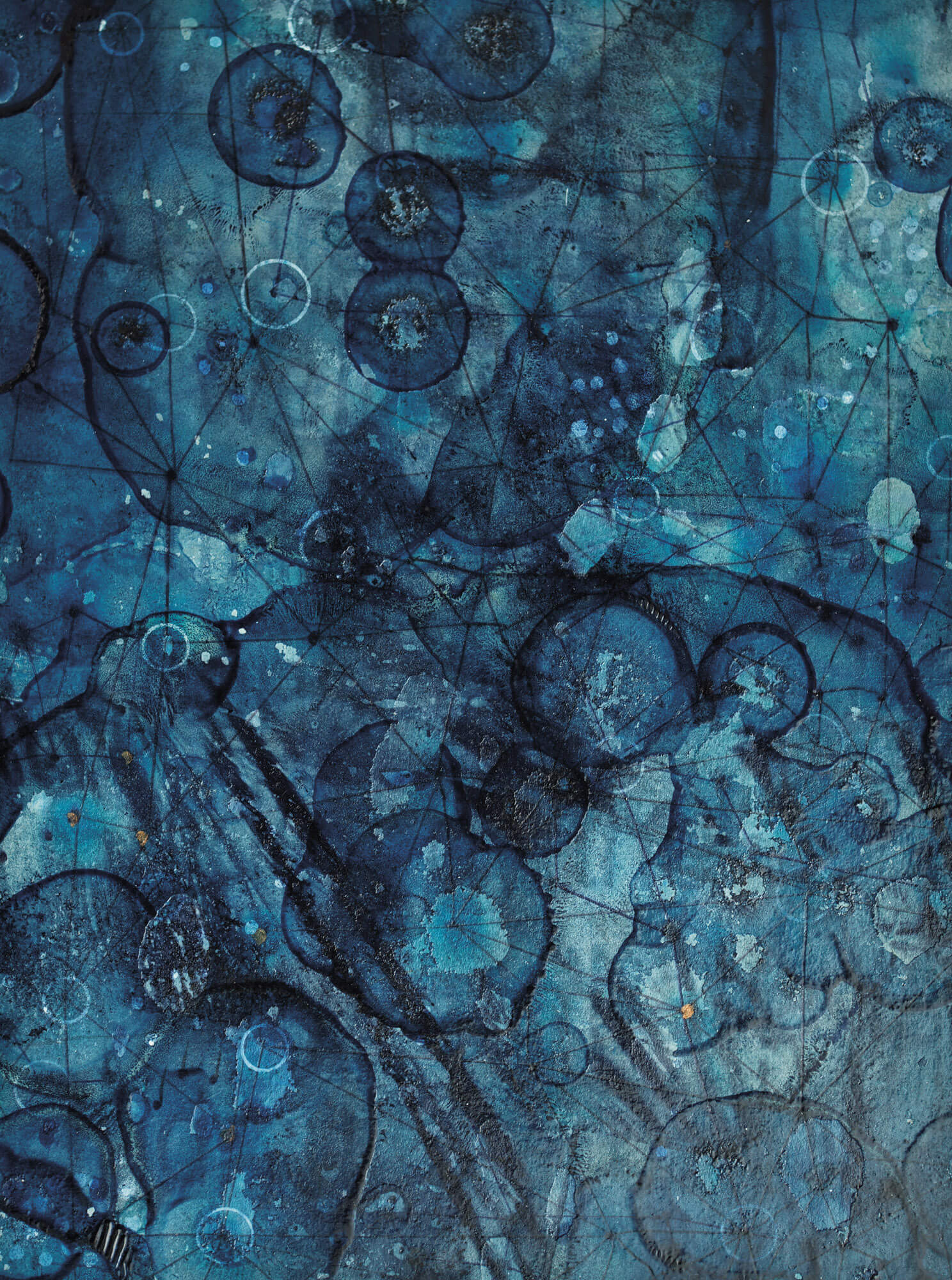

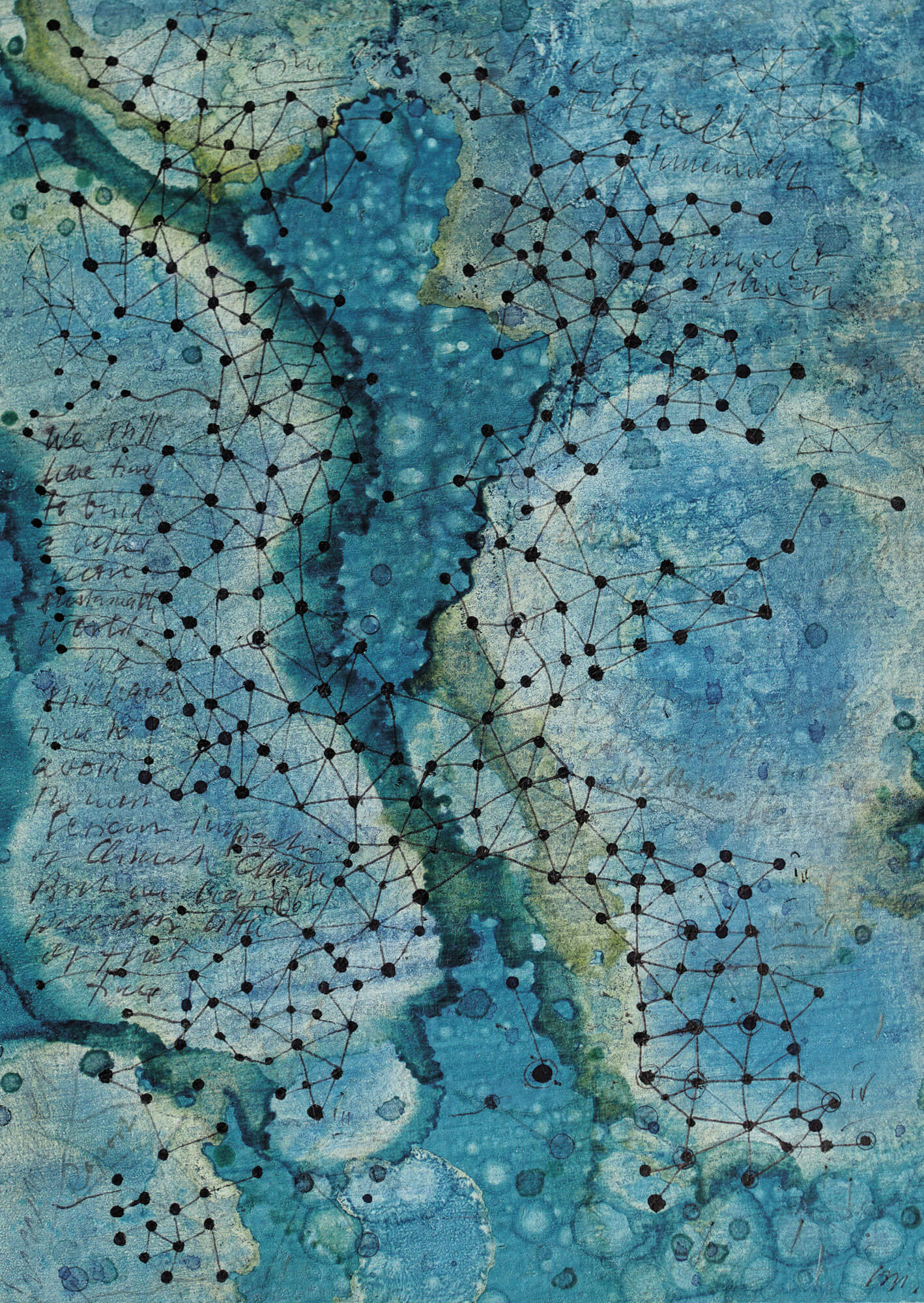

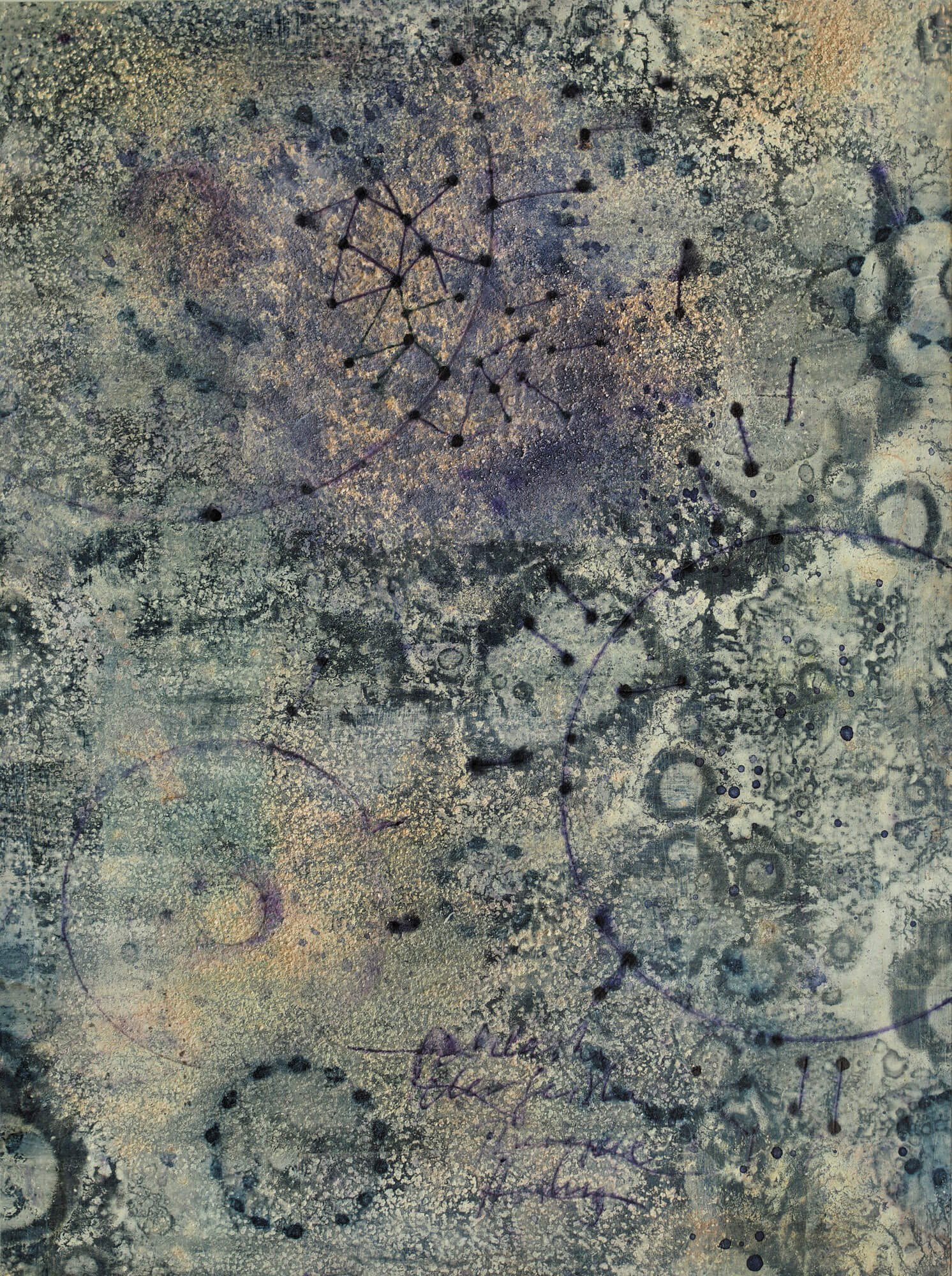

George SteinmannBio

The Soul of Remedies seeks to raise awareness of the aesthetic

dimension of our current eco-crisis, together with the subtle beauty of biodiversity and the

beneficial power concealed within it. Alpine plants, grass and natural remedies are positive and

negative indicators of the relationship between humans and mountain ecosystems.

The materials sourced in the Swiss Alps comprise medicinal plants such as European blueberry

(Vaccinium myrtillus), nettle (Urtica dioica), fern (Pteridophyta) and lichen

(Letharia vulpina)

but also mineral water essences, obtained by the artist directly from sources in the lower

Engadin valley in Switzerland, and bioindicators such as beeswax and mistletoe. All natural

materials linked to a holistic perception of the mountain environment.

In his research, George Steinmann studies and spreads knowledge of the long-standing tradition

of natural remedies and homeopathic treatment methods

in the alpine culture. This transdisciplinary practice originated after the realisation

that a greater holistic knowledge and sensitivity can boost a sense of responsibility towards

our habitat and the sense of reconnecting with Mother Earth. But also the invitation addressed

to science to broaden its horzon of research, to provide scientific evidence on unexplored

topics.

Mountains as Sentinels

Italy is a mountain country that thinks it is lowland. This false perception gives rise

to many of the natural disasters that afflict the country, such as the neglect of

environments that we literally owe our lives to.

Recent studies, coordinated by Andrea Piotti, a researcher at the Italian National

Research Council (CNR), have demonstrated that the genetic preservation of certain

species of mountain plants from the Alps, Apennines, Pyrenees and Dinaric Alps is one of

the key measures in the attempt to overcome the incipient bottleneck of climate changes

and ecological crisis.1, 2 Silver fir plays a special role

because, thanks to its resilience and capacity to propagate in southern Europe’s glacial

refuges, it is able to guarantee the survival of mountain forests in the face of the

harshest climate changes.

On the other hand, a bush like blueberry, with its small delicate fruit, provides

irreplaceable ingredients for excellent recipes in the kitchen but also for food

supplements with proven efficacy against major diseases, such as venous insufficiency,

microcirculation issues and syndromes affecting vision, for example degenerative

maculopathy.3

Equally, oligomineral waters, an irreplaceable font of minerals for our organism, rise

almost exclusively from mountain springs.

Mountains are sentinels – from their summits you can see further – so it is no surprise

to learn that for several years now both the CNR and the CAI (Italian Alpine Club) have

been carrying out a project whose results will be welcomed by future generations. The

“Rifugi sentinella del clima e dell’ambiente” project4 is a

network of high-altitude monitoring stations in the Alps and Apennines that aims to

grasp in advance, like a real time machine, the signals of climate change, including

Alpine glaciers, and of atmospheric composition, thus enabling us to promptly adopt

measures to counteract them, or at least reduce their consequences.

It will be no surprise either to learn that these stations also monitor the quality of

the night sky. No less than air pollution, light pollution – which also illuminates the

mountain sky from the populous plains – is a pressure as undue as it is dangerous for

the health both of high-altitude plants, grasslands and fauna and of human beings.5, 6

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- A. Piotti, C. Leonarduzzi, D. Postolache, F. Bagnoli, I. Spanu, L. Brousseau, C. Urbinati, S. Leonardi, G. G. Vendramin, “Unexpected scenarios from Mediterranean refugial areas: disentangling complex demographic dynamics along the Apennine distribution of silver fir”, Journal of Biogeography, 44, 2017, pp. 1547–1558. LINK→

- E. Vajana, M. Andrello, C. Avanzi, F. Bagnoli, G. G. Vendramin, A. Piotti, “Spatial conservation planning of forest genetic resources in a Mediterranean multi-refugial area”, Biological Conservation, 293, 110599, 2024. LINK→

- P. Jaglan, H.S. Buttar, O. A. Al-bawareed, S. Chibisov, “Potential health benefits of selected fruits: apples, blueberries, grapes, guavas, mangos, pomegranates, and tomatoes. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals in Metabolic and Non-Communicable Diseases”, Academic Press, 2022. LINK→

- LINK→

- L. Massetti, F. Meneguzzo, “Il cielo naturale notturno. Il Bollettino Del Comitato Scientifico Centrale, Aprile”, 2022, pp. 122–128. LINK→

- E. Mazzoleni, M. Vinceti, S. Costanzini, C. Garuti, G. Adani, G. Vinceti, G. Zamboni, M. Tondelli, C. Galli, S. Salemme, S. Teggi, A. Chiari, T. Filippini, “Outdoor artificial light at night and risk of early-onset dementia: A case-control study in the Modena population, Northern Italy”, Heliyon, 9(7), 2023. LINK→

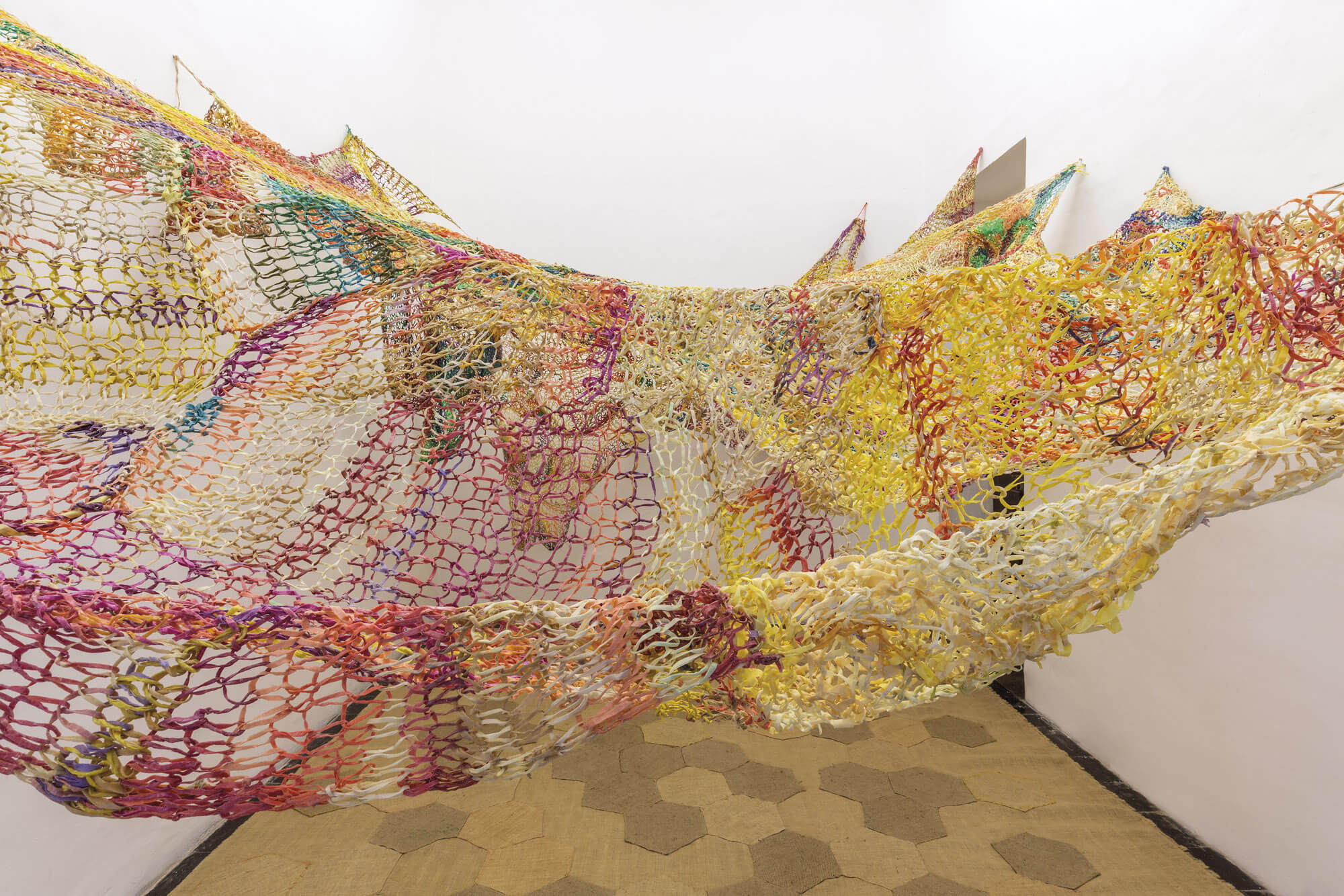

Paola AnzichéBio

In her practice Paola Anziché creates soft, tactile sculptures stemming from a research process

that explores the potential of art to establish relationships with various cultural spheres such

as anthropology, ancient ritual, bio-architecture and science. Her curiosity prompts her to

travel and enter into contact with different traditions, which she then reinterprets. Manual

work, gesture and an attentiveness to the materials employed, with a special focus on natural

ones, are at the heart of her method, which is also performative and participatory.

Adopting a slow process involving the immersion of coloured natural fabrics in liquid wax, their

drying and subsequent weaving, Paola Anzichè created La terra suona, a soft sculpture

evoking

the form of a large beehive. In this welcoming space, the juxtaposition of delicate colours is

reminiscent of a flowering meadow in spring, the fragrance of which permeates onlookers, acting

on their bodies and minds.

Visitors are invited to lie on a jute rug, the texture of which echoes the hexagonal shape of

beehive cells, and live a multisensorial and therapeutic experience.

Paola Anziché

La terra suona, 2022

Waxed fabric and jute; beehive rug made with jute

Courtesy the artist

Ecosystem Connections, Forests and Eating Habits

Even more so than by human interconnections, by transport and by the Internet, our planet

is strongly interconnected by its most important terrestrial ecosystems: the great

natural or unmanaged forests, now an almost exclusive heritage of the low and high

latitudes, which provide carbon sequestration and climate stability.

A complex study on forest ecosystem networks has shown that if the distance separating

two large forest ecosystems increases beyond a certain limit, for example due to

deforestation, at least one of these ecosystems may precipitate towards extinction,

amplifying the extent of the deforestation itself.1

Furthermore, only unmanaged forests are, via their free evolution, able to optimise the

proportion of old and young trees, allowing the forest itself to prosper and provide all

its services. By contrast, reforestation with young trees does not allow a recovery of

the function of an important mechanism called the “biotic pump”.2,

3 Still subject to research and verification, this mechanism consists in

“recycling” ocean vapour over distances of thousands of kilometres, thanks to complex

effects of moisture transpiration from forests on atmospheric circulation.

It has also been demonstrated that the transition of the human diet from animal protein

to vegetable protein would bring huge savings in the consumption of the ground, water,

and greenhouse gas emissions.4, 5 Obtaining food of animal

origin by means of intensive farming (which is necessary for producing animal feed)

requires a ground and water consumption of between 2.4 and 33 times greater and

generates between 2.4 and 240 times more greenhouse gas emissions than a production

system oriented towards the consumption of vegetable protein alone. The essential reason

is that only 15% of the vegetable protein provided by crops and destined for animal feed

is transformed into equivalent animal protein for human consumption. About 85% of the

original vegetable protein is lost due to normal animal metabolism: only a small part of

the ingested protein is transformed into animal protein, the rest being destined for

other functions of the organism. Directly consuming the vegetables grown allows access

to 100% of the relative proteins as well as the precious bioactive compounds of which

they are rich and that make major contributions to our health. If not the solution to

the climate problem, altering global eating habits is at least necessary in order to

liberate large areas to allocate to the expansion of natural forests, to cut greenhouse

gas emissions and so counter climate change.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- G. Cantin, N. Verdière, “Networks of forest ecosystems: Mathematical modeling of their biotic pump mechanism and resilience to certain patch deforestation”, Ecological Complexity, 43, 2020. LINK→

- A. M. Makarieva, A. V. Nefiodov, A. D. Nobre, M. Baudena, U. Bardi, D. Sheil, S. R. Saleska, R. D. Molina, A. Rammig, “The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence”, Global Change Biology, 29(9), 2023, pp. 2536-2556. LINK→

- E. Gies, “More than carbon sticks”. Nature Water, 1(10), 2023, pp. 820– 823. LINK→

- A. Di Paola, M. C. Rulli, M. Santini, “Human food vs. animal feed debate. A thorough analysis of environmental footprints”, Land Use Policy, 67, 2017, pp. 652–659. LINK→

- S. V. Ramesh, S. Praveen, “Conceptualizing Plant-Based Nutrition: Bioresources, Nutrients Repertoire and Bioavailability”, in S. V. Ramesh & S. Praveen (Eds.), Conceptualizing Plant-Based Nutrition: Bioresources, Nutrients Repertoire and Bioavailability, Springer Nature, 2022. LINK→

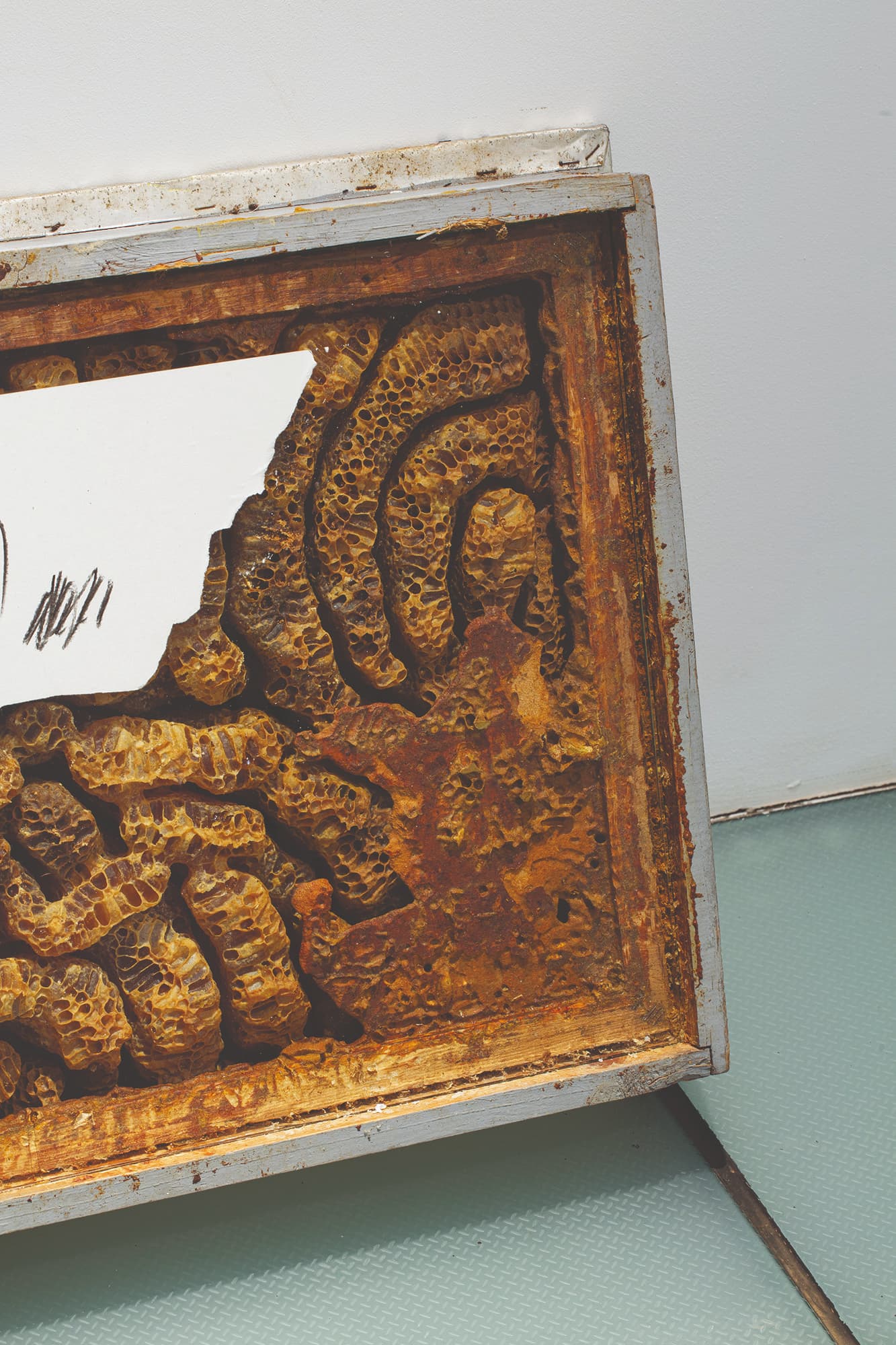

Fernando García-DoryBio

Fernando García-Dory is the founder of INLAND, a collective formed in Spain in 2009 to

collaboratively rethink the relationships between rural life and culture. Here he has developed

beehives to protect bees and provide the locals with honey and healthy produce such as propolis

and royal jelly.

An Apiary for the Inland Village forms part of a broader project envisaging the

creation of a

beehive and a cabin as a space of healing and encounter between knowledge and species. A place

where the use of the healing and therapeutic powers of the apiary – driven by the presence of

aromatic wax, honey, pollen and propolis vapours, micro-vibration and the sound frequency of

bees buzzing, a stable physiological temperature and the ionisation of the air – have a

beneficial impact on human beings.

The audio installation presents a soundscape where the sound produced by the bees, which has

healing properties thanks to its frequencies and that science is trying to prove, is

interspersed with a chorus of women engaged in the traditional practice of “telling the bees”

about a death in the family, with a view to avoiding further loss.

In dialogue with the other works present, this one celebrates the force of the bees and the

therapeutic dimension this species manages to generate at different levels, in both the human

sphere and in the biological processes of the natural world.

INLAND / Fernando García-Dory

An Apiary for the Inland Village,

2021

Sound installation

Courtesy INLAND – Campo Adentro

In collaboration with Antooloops

Safeguarding Soundscapes

The human sense of hearing is one of the principal mediators of the beneficial effects

produced by forest immersion. This is arguably further confirmation of the “biophilia”

hypothesis1 secondo cui l’ambiente

naturale, dove Homo sapiens whereby the natural environment in which Homo

sapiens lived for much of our evolutionary history, requires the least effort

to focus,

thus allowing thoughts to flow and a return to ourselves. Natural sounds are capable of

alleviating stress, anxiety and agitation, affecting the parasympathetic activity of the

nervous system, as demonstrated also by an improvement in a number of physiological

indicators, such as the level of skin conductance, and heart rate frequency and

variability.2 The sound of wind through leaves, birdsong and

particularly running water have the power to induce relaxation and well-being,

especially if not “sullied” by artificial noise, whether of a busy street or a chainsaw.

Indeed, in the case of sound stimuli, “environmental coherence” is very important:

namely the absence of disturbing “out of context” factors and, on the contrary, the

presence of expected elements in a forest area (for example, watercourses in mountain

zones; uncontaminated forest sounds; natural or re-naturalised forest structures, and so

on).

The importance of the sound component in contributing to the effects of recovery linked

to visiting natural environments has only been recognised in recent times, partly

because many studies traditionally focused on the visual component. Recent evidence

demonstrates that, in laboratory situations in which sensorial (visual and auditory)

input was isolated, the auditory stimuli were even more efficacious than exposure to

visual stimuli alone.3

As well as sounds produced by trees and running water, the sonorous forest environment

consists in sounds produced by fauna, winged in particular, including bees. Some argue,

although we await convincing scientific proof, that the particular frequencies, between

400 and 500 Hz, of bee humming favour a particular mental and physical relaxation. What

is instead certain is the great benefit produced by the sounds of the forest all

together, so long as not contaminated by artificial noise.4

Acoustic pollution, on a par with that of light, is now ubiquitous and pervasive. The

impact on our health is often underestimated, or at least considered an inevitable

legacy of our urban lives, annoying but unavoidable.

Actually, prolonged exposure to even low-level noise is, in a strict sense, a public

health problem. It has long-term repercussions both on hearing functions and on several

mental functions, such as concentration and memory, contributing to conditions of stress

and therefore increasing cardiovascular risks.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.6 million healthy life years are

lost every year from traffic-related noise in western Europe. Sleep disturbance, a rise

in the levels of “stress hormones” and oxidative stress in the vascular system and the

brain can favour vascular dysfunction, inflammation and hypertension, increasing risks

of cardiovascular diseases.5

As well as safeguarding increasingly rare natural soundscapes, it is hoped that a focus

on the sound component will become an integral part of “restorative” landscape design,

for example in city parks, so that they may best perform their functions of reducing and

acting as an antidote to stress.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- E. O. Wilson, Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- H. Jo, C. Song, H. Ikei, S. Enomoto, H. Kobayashi, Y. Miyazaki, “Physiological and Psychological Effects of Forest and Urban Sounds Using High-Resolution Sound Sources”, International Journal of Environmental. Research and Public Health 16, 2019. LINK→

- C. Song, H. Ikeib, H. Miyazaki, “Effects of forest-derived visual, auditory, and combined stimuli”, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 64, 2021. LINK→

- P. Fiľo, O. Janoušek, “Differences in the Course of Physiological Functions and in Subjective Evaluations in Connection With Listening to the Sound of a Chainsaw and to the Sounds of a Forest”, Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 2022. LINK→

- T. Münzel, M. Sørensen, A. Daiber, “Transportation noise pollution and cardiovascular disease”, Nature Review Cardiology, 18, 2021, pp. 619–636. LINK→

Lucas FogliaBio

Lucas Foglia grew up on a small farm 50 kilometres east of New York City. His family has always

lived off what it grew and used barter as a means of exchange. They have maintained a special

relationship with nature, shielded from the dynamics of shopping malls and urban contexts. For

the artist, the forest adjoining their farm was a wild land to be explored, a place unknown to

the neighbours who were Manhattan commuters. The relationship between modernity and nature,

between human beings and their habitat – be it natural or manmade – are the fulcrum of all the

American photographer’s research.

Human Nature is a photographic tale, of which eight pictures are on show in the

exhibition. It

explores the relationship between human beings and nature through a multifocal gaze. Sometimes

with irony and other times with a certain melancholy, the images speak of the present and the

future, the need to find a connection with nature and with the wild side that resides in all of

us. Every story is set in a different ecosystem: city, forest, mountain, farm, desert, glacier,

ocean and volcano. Human Nature tells how nature is today both cure and threat at the

same time.

As we spend ever more time at home staring at screens, neuroscientists are demonstrating that

time spent in the open air is vital for human health and happiness. The photographs explore our

need for wild places as therapeutic spaces in the Anthropocene epoch while also reminding us

that as a result of manmade impact they have become formidable, making us vulnerable to storms,

drought, heatwaves and freezing.

Artificial Environments, Mental Health and Natural Solutions

In 2019, 970 million people, that is 13% of the world’s population, were living with

mental illness.1 In Europe, according to the last data

relative to 2016, mental health issues affected one person in six, with a cost of 600

billion euros, or more than 4% of GDP. The most common mental illnesses in European

countries are anxiety disorders (5.4% of the population), followed by depressive

disorders (4.5%) and disorders linked to drug and alcohol abuse (2.4%).2

Mental health issues are a growing problem in urban areas and various studies suggest

that urban life is a risk factor that undermines health and mental well-being.3 City residents have greater probFOGLIAabilities of being

exposed

to environmental stress factors, such as traffic, noise and atmospheric pollution,

which, in their turn, affect the psychophysiological system. At the same time, town

dwellers are less exposed to the natural environment, due in the first place to a

limited availability of green spaces in cities, and therefore to their beneficial and

restorative effects.

Over the last few years, the relaxing and restorative effects of the natural environment

have gradually gained attention, partly thanks to the development of medical measuring

tools that facilitate the accumulation of scientific proof based on physiological

parameters.

Recognition of the health value of “nature-based” practices ultimately offers a major

opportunity to integrate traditional medical care with preventive and therapeutic

practices also accessible to people on a low income – often more prone to the risk of

mental illness.

As well as on individual and public health, these effects are also extremely positive in

terms of saving on healthcare costs. A major study conducted in 2019 demonstrated that,

in terms of the costs avoided for the visitors’ mental health, the overall annual value

of visiting protected natural areas, such as national parks, amounts to approximately 8%

of GDP in the more industrialised countries, i.e. up to a thousand times the budget

assigned to the conservation of those same protected natural areas.4 This is less, but always above the 4%, in less

industrialised countries, where the technosphere is not yet so invasive, although in

inexorable expansion.5

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- T. L. Osborn, C. M. Wasanga, D. M. Ndetei, “Transforming mental health for all”. British Medical Journal, 2022. LINK→

- A. Ventriglio, J. Torales, J.M. Castaldelli-Maia, D. De Berardis, D. Bhugra, “Urbanization and Emerging Mental Health Issues”, CNS Spectrums 2021, 26, 2021, pp. 43–50. LINK→

- OECD/European Union (2022), "Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle”, OECD Publishing, Paris, LINK→

- Buckley R., et al. (2019). “Economic Value of Protected Areas via Visitor Mental Health”. Nature Communications, vol. 10, no. 1. LINK→

- R. Buckley, et al., “Economic Value of Protected Areas via Visitor Mental Health”.Nature Communications, 10 (1), 2019. LINK→

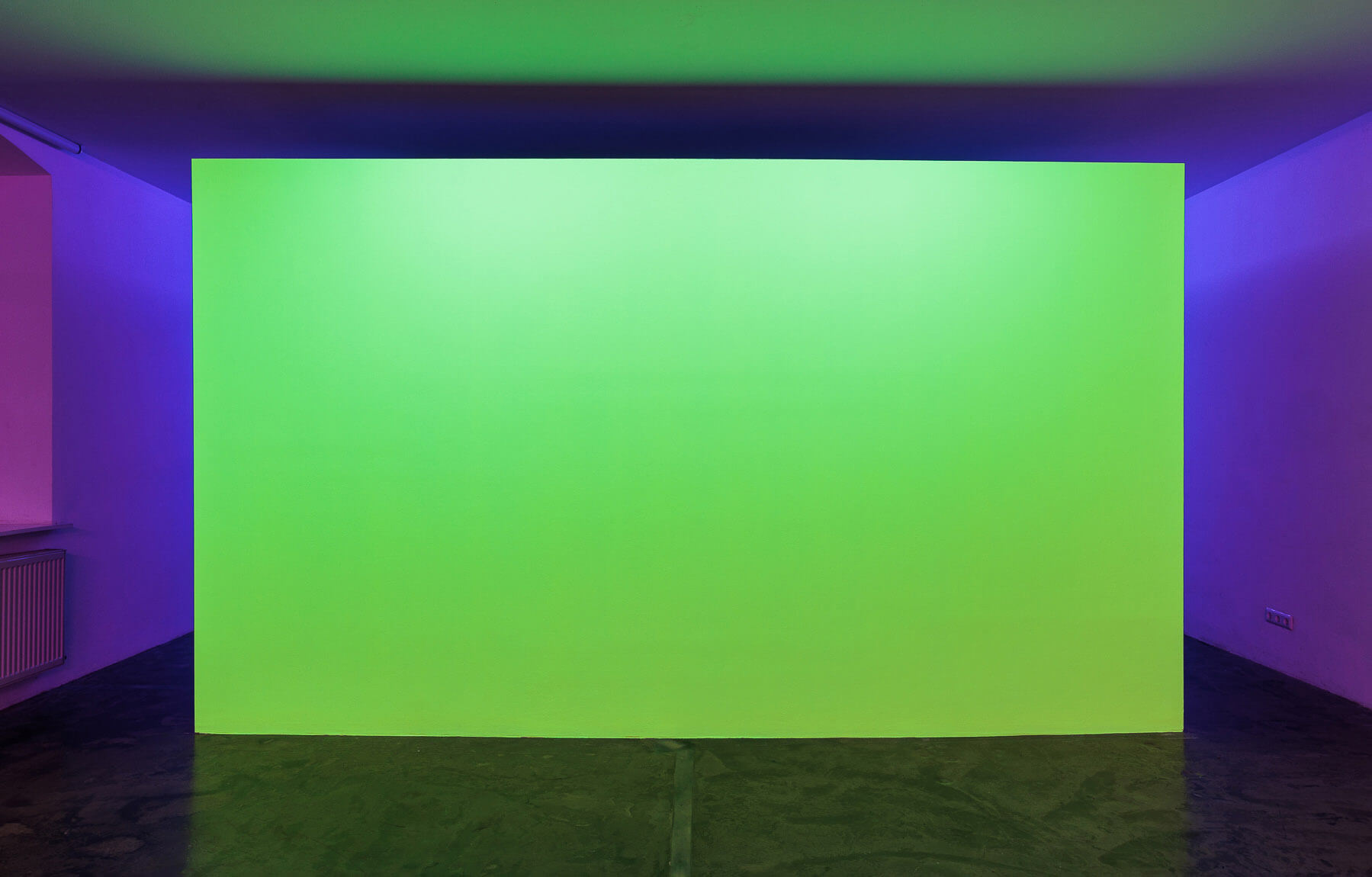

Zora KreuzerBio

Zora Kreuzer’s research is focused on colour and explores the aesthetic and conceptual potential

that arise from its use. Through works of an environmental nature, in which pigments and colours

are placed to dialogue with light, the artist leads spectators into immersive and multi-sensory

experiences. Formally minimal but technically based on a principle of dynamics, her works are

developed from the phenomenon of electromagnetic radiation, exploiting a wavelength between 380

and 760 nanometres, in other words light that human vision can perceive. Perceptive and

physiological effects, such as flickering colours (via juxtaposing highly contrasting colours),

the appearance of after-images (after prolonged observation of a colour, its complementary

colour becomes visible when we close our eyes), or the perceived reduction in colour intensity

when the eyes become accustomed to it, are only some examples of phenomena that repeatedly occur

when observing her site-specific works.

The mixing of values such as intensity, tonality, nuancing and temperature – skilfully codified

by the artist – restores a fluid visual dimension, in which the feeling of observing a

constantly evolving nuance is perceptible.

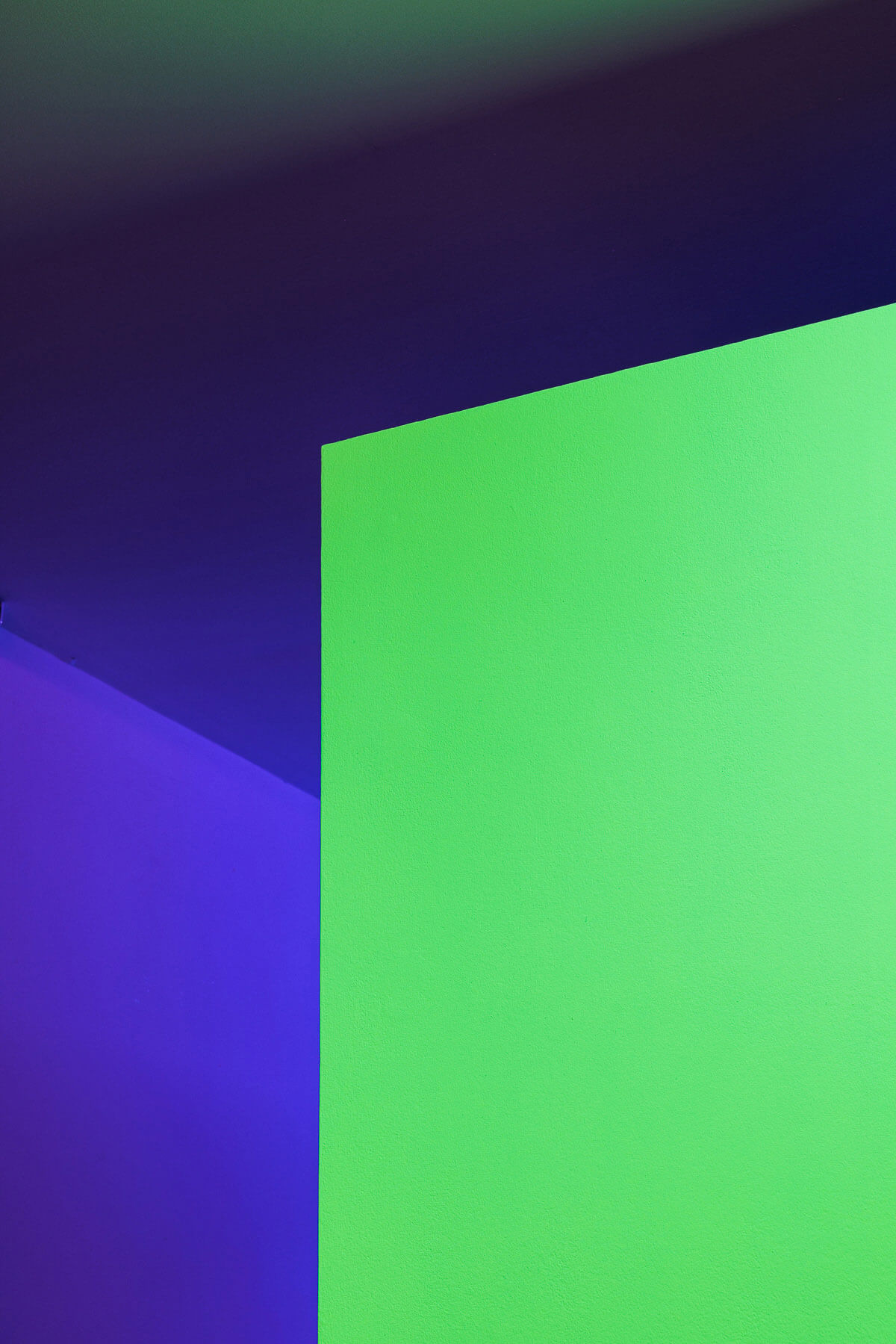

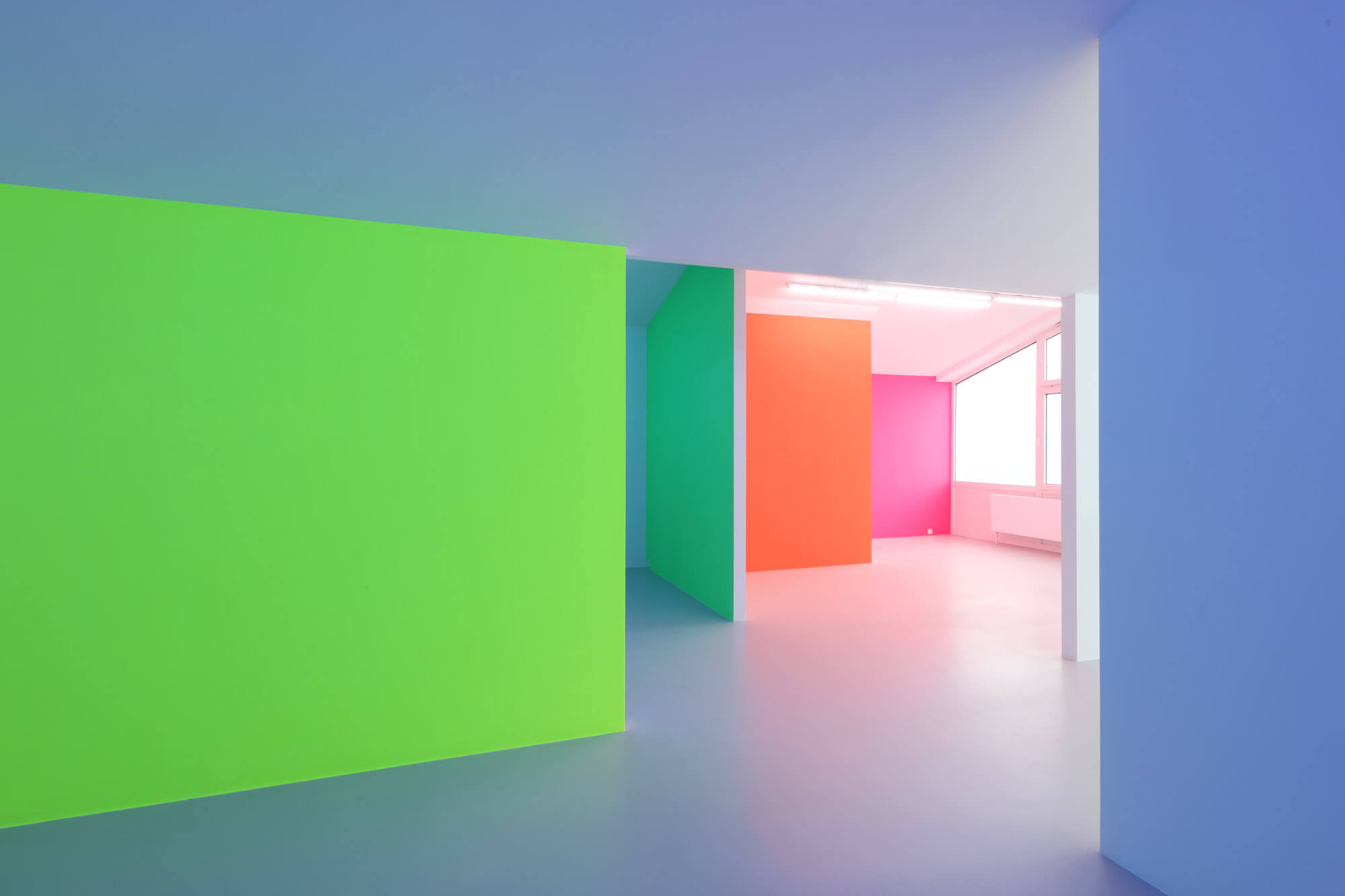

In the installation Green Room, Zora Kreuzer intervened on the walls of the space with

a coat of

green paint, whose refraction is emphasised by the use of ultraviolet light transmitted by a LED

lamp.

Produced as part of the research conducted by scientists of the Neuroscience Institute Cavalieri

Ottolenghi of the University of Turin on the impact that the colour green has on human beings,

the work was conceived as a sort of colour bath.

Green Room artificially proposes an accentuated experience of the perceptive and

sensorial

stress we are subjected to when we observe and come into contact with the colour green, which is

present in a natural contest, as in mountains. The work raises a series of questions to which

science is attempting to respond: how do our senses react when we come into contact with green?

How does this colour, in all its gradients, affect our psycho-physical well-being? After how

long is it possible to detect an alteration in our vital parameters in response to being exposed

to it? And for how long? What kind of scenarios does scientific confirmation of such a positive

relation open up?

Zora Kreuzer

Green Room,

2024

Dispersion paint on wall, ultraviolet light, LED lamp

Courtesy the artist

Our brain interprets different wave lengths of visible light as colours. In our daily

life, we are used to associating important information about our surrounding environment

with colours: for example, if we see a red berry we are inclined to think it is

poisonous and so dangerous for our health. Colours, therefore, guide our attention and

choices, helping us to survive. It is an ancestral trait, but our brain still does

everything it can to detect and identify them.

Colours are also capable of triggering emotions and conditioning our mood and state of

well-being. In particular, “cold” colours (such as green and blue) induce a relaxing

effect that entails real physiological changes. For example, we know that immersing

ourselves in nature brings us an immediate feeling of psycho-physical well-being. Until

a few years ago, this concept was based solely on empirical observations, but today

scientific evidence demonstrates that exposure to natural environments can generate real

changes in our body, such as modifications in our blood pressure, heart rate and immune

system functioning.1 However, effects on our mental health

are even more evident: being immersed in greenery triggers feelings of happiness and

well-being and reduces anxiety and depression, modifying our levels of

neurotransmitters, hormones and molecules responsible for stress.2 This is why doctors and surgeons often wear green or blue,

in an attempt to put their patients more at ease. Furthermore, wearing lenses that

filter certain colours can change our electroencephalographic waves and reduce

anxiety.3 These physical reactions are also borne in mind by

advertising agents in the so-called “neuromarketing” field, a branch of marketing that

studies the cognitive aspects of consumers in order to influence their preferences and

acquisitions. Furthermore, phototherapy can have effects on circadian rhythms, on the

expression of GABAergic or glutamatergic cells and on the perception of pain.4 Green spaces in cities are associated with positive

emotions, mindfulness and relaxation.

But it is not only looking at and contemplating greenery that gives us a sense of

relaxation whenever we walk through woods. It has now been established5 that some plants can release volatile substances called

terpenoids and terpenes (among which pinene and limonene), capable of inducing

beneficial responses throughout our body, which underlie the effects of forest bathing.

As well as showing strong antioxidant and anti-neuroinflammatory activity, some of these

substances also seem to be neuroprotective.6

Attempting to harness the benefits of immersion in greenery even for people who have no

direct access to nature, virtual multisensory “immersive” technologies might become ever

more relevant.

— Marina Boido e Alessandro Vercelli

Neuroscience Institute Cavalieri Ottolenghi, University of Turin

- K. K. Yau, A. Y. Loke, “Effects of forest bathing on pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults: a review of the literature”, Environ Health Prev Med, 2020. 10.1186/s12199- 020-00856-7.

- B. J.Park, C. S. Shin, W. S. Shin, C. Y. Chung, S. H. Lee, D. J. Kim, Y. H. Kim, C. E. Park, “Effects of Forest Therapy on Health Promotion among Middle-Aged Women: Focusing on Physiological Indicators”, Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124348.

- K. Boere, O. E. Krigolson, The effects of multi-colour light filtering glasses on human brain wave activity, BMC Neurosci, 2024. doi: 10.1186/s12868-024-00865-0.

- X. Q. Wu, B. Tan, Y. Du, L. Yang, T. T. Hu, Y. L. Ding, X. Y. Qiu, A. Moutal, R. Khanna, J. Yu, Z. Chen, “Glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in the vLGN mediate the nociceptive effects of green and red light on neuropathic pain”, Neurobiol Dis, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2023.106164.

- K. S. Cho, Y. R. Lim, K. Lee, J. Lee, J. H. Lee, I. S. Lee, “Terpenes from Forests and Human Health”, Toxicol Res, 2017. doi: 10.5487/TR.2017.33.2.097

- B. Xu, L. Bai, L. Chen, R. Tong, Y. Feng, J. Shi, “Terpenoid natural products exert neuroprotection via the PI3K/Akt pathway”, Front Pharmacol, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1036506.