Section 2

Ruben BrulatBio

Ruben Brulat’s works are nearly always born out of a travel experience and a journey undertaken

by the artist to reach some of the remotest parts of the world. Nature is where and how Brulat

pursues his personal need to understand where and why we exist.

His pictures depicting his camouflaged naked body in the mountains, forests, deserts, volcanos

and glaciers are famous – unpolluted environments where the fusion between human being and

natural elements is manifested via actions of a performative nature. The attempt to connect with

the earth, feel its substance and become one with nature evoke sentiments of both strength and

fragility.

In the video Doigt, voir dans le vert des jungles, filmed in the forests of the

Ruwenzori

mountain range in Africa, the camera focuses on the moment when the artist’s finger enters into

contact with the vegetation. The act has an alchemic feel of the encounter between human body

and the primary forces of nature.

Ruben Brulat

Rouge Hanche, 2022

Giclée Hahnemühle Photo Rag Pearl

Courtesy the artist and Ncontemporary, Milan-London-Venice

Forests for Climate Stability

Services rendered by trees to our planet range from carbon sequestration to the

production of oxygen, to the conservation of the ground and the regulation of the water

cycle. Trees support both natural and human food systems and provide shelter for

numberless species, humankind included, via construction materials.

While all forest ecosystems are important, tropical forests are essential for the

planet’s equilibrium and for the very survival of the human species.

Apart from the loss of an important player in atmospheric carbon sequestration,

deforestation and forest degradation in the great tropical forests cause serious

environmental impact, also thanks to their effects on climate regulation.1

Since 1990, primary forest surface – now present only in tropical and boreal zones – has

diminished by more than 80 million hectares and more than a third of the forest surface

has been lost compared to the time before the development of human civilisation.2

Carbon sequestration is the first and most evident

service offered by our global forests. But they also play an even more important role in

climate stability, thanks to their releasing large quantities of water vapour into the

atmosphere that, by diminishing air pressure in the lower atmosphere, facilitates the

flow of moist air from the oceans. Known as the “biotic pump” and postulated first by

two Russian physicists, this mechanism is capable of transporting water vapour over huge

distances far from the oceans, thus guaranteeing rainfall in many inland areas.3 In South America, the River Plate basin depends on

evaporation from the Amazon rainforest for 70% of its water resources, and western

China, which has the largest expanses of cereal crops, depends for over 80% of its

waters resources on humidity recycled from the Euro-Asiatic forests (from Scandinavia to

east Russia).4

This capacity for climate regulation is guaranteed above all by the great natural or

unmanaged forests that are not disturbed by human actions. To safeguard them should be

an absolute top priority within the context of the progressive changes of the global

climate.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- E. Gies, “More than carbon sticks”, Nature Water, 1(10), 2023, pp. 820–823. LINK→

- M. Bologna, G. Aquino, “Deforestation and world population sustainability: a quantitative analysis”, Scientific Reports, 10(1), 2020, 7631. LINK→

- A. M. Makarieva, A. V. Nefiodov, A. D. Nobre, M. Baudena, U. Bardi, D. Sheil, S. R. Saleska, R. D. Molina, A. Rammig, “The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence”, Global Change Biology, 29(9), 2023, 2536–2556. LINK→

- R. J. Van Der Ent, H. H. G. Savenije, B. Schaefli, S. C. Steele-Dunne, “Origin and fate of atmospheric moisture over continents”. Water Resources Research, 46(9), 2010.LINK→

Bianca Lee VasquezBio

Bianca Lee Vasquez’s research is focused on formalising invisible aspects and nuances that we

often do not notice. Fascinated by the deep bond that links human beings to everything that

surrounds us and conscious of the natural forces that interact with our biological and mental

aspects, the artist gives shape to installation-type works that oblige us to look at reality.

Using her body, both as a physical presence (the artist often proposes performative actions) and

evoked in a symbolic way, is a cornerstone of her practice.

In Dirt High Series, Bianca Lee Vasquez brings a quantity of fertile composted earth

into the

gallery space onto which she places terracotta figures. With their sinuous forms and archaic

appearance, they recall concepts of femininity, fertility, symbiosis and metamorphosis.

The artist evokes the primordial symbiotic bond that ontologically links human beings to the

Earth, bringing to mind knowledge and perceptions of archaic civilisations that are still very

strong in indigenous populations.

Referring to the theme of the exhibition, the work questions a series of recent scientific

studies: firstly those centred on investigating the antidepressive effect on the human mind of

the bacterium Mycobacterium vaccae, present in the ground and capable of generating a

feeling of

happiness thanks to an increase in serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the blood. And

secondly those concerned with the beneficial impact on cerebral activity of geosmin, a substance

produced by various classes of micro-organisms, among which cyanobacteria and actinomycetes,

released into the air via an aerosol of minuscule particles when rain drops touch the ground,

generating the typical smell of rain and wet earth, technically known as “petrichor”.

Bianca Lee Vasquez

Dirt High Series, 2021–2024

Installation

Courtesy the artist and Sainte Anne Gallery, Paris

Smell, the “Primordial Sense”

The nose can be considered the most external part of our brain.

In the olfactory epithelium, olfactory sensory neurons are present, whose receptors

receive odorous stimuli and then transmit them directly to the cerebral cortex, without

the mediation of the thalamus, as occurs for other sensorial systems.

Unlike other neurons, olfactory neurons can constantly regenerate to counteract the

dangers deriving from their external position (attack from external agents such as

viruses, bacteria).

Among the areas of the brain that are directly activated by olfactory neurons, some make

up part of the limbic system – such as the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus – and

are closely linked to processing emotions and memory. This extensive olfactory network

demonstrates the importance held by the sense of smell for mediating physiological and

behavioural responses to emotionally stimulating events in many animals. It also

explains why smell has such a rapid effect on modulating emotional responses, and why it

is the most efficient of the senses to evoke memories.1-3

In 1964, the Australian researchers Isabel J. Bear and Richard G. Thomas published an

article in Nature in which they used the term “petrichor” – petros (stone) and

ichor

(blood of the gods) – to describe the smell of rainwater on dry earth.4 The olfactory phenomenon, made possible by the atmospheric

aerosol documented by the two scientists, originates from the diffusion into the air of

essential oils (produced previously by plants) from fungal spores, bacteria and geosmin

present in geological material.

More recently, scientists at MIT in Boston demonstrated that a greater quantity of

aerosol is produced on porous rocks and when the rain falls slowly rather than quickly,

since these conditions give the air trapped in the geological material more time to be

vaporised into the air.5

In much less urbanised environments, such as mountains, geosmin prevails over the

presence of ozone in the air and is therefore perceived more intensely. This is why that

particularly earthy smell is perceived in mountains as soon as it rains. Numerous

international studies are analysing the positive effects of petrichor and geosmin on the

cerebral activity of human beings. Researchers at the School of Natural Resources and

Environmental Sciences in South Korea and at the Department of Neurology and Behaviour

at Stony Brook University in New York have concluded that they are capable of generating

profound emotions that calm the mind and alleviate anxiety.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- D. H. Brann, S. R. Datta, “Finding the Brain in the Nose”, Annu Rev Neurosci. 43, 2020, 277-295. LINK→. PMID: 32640927.

- M. Catani, F. Dell’acqua, M. A. Thiebaut de Schotten, “A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behavior”, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 2013, pp. 1724–1737. LINK→

- G.N. Bratman, et al., “Nature and Human Well-Being: The Olfactory Pathway”, Science Advances, 2024, 10 (20). LINK→.

- I. J. Bear, R. G. Thomas, “Nature of Argillaceous Odour”, Nature, 201(4923), 1964, 993–995. LINK→

- Y. S. Joung, C. R. Buie, “Aerosol generation by raindrop impact on soil”, Nature Communications, 6, 2015, 6083. LINK→.

Caterina MorigiBio

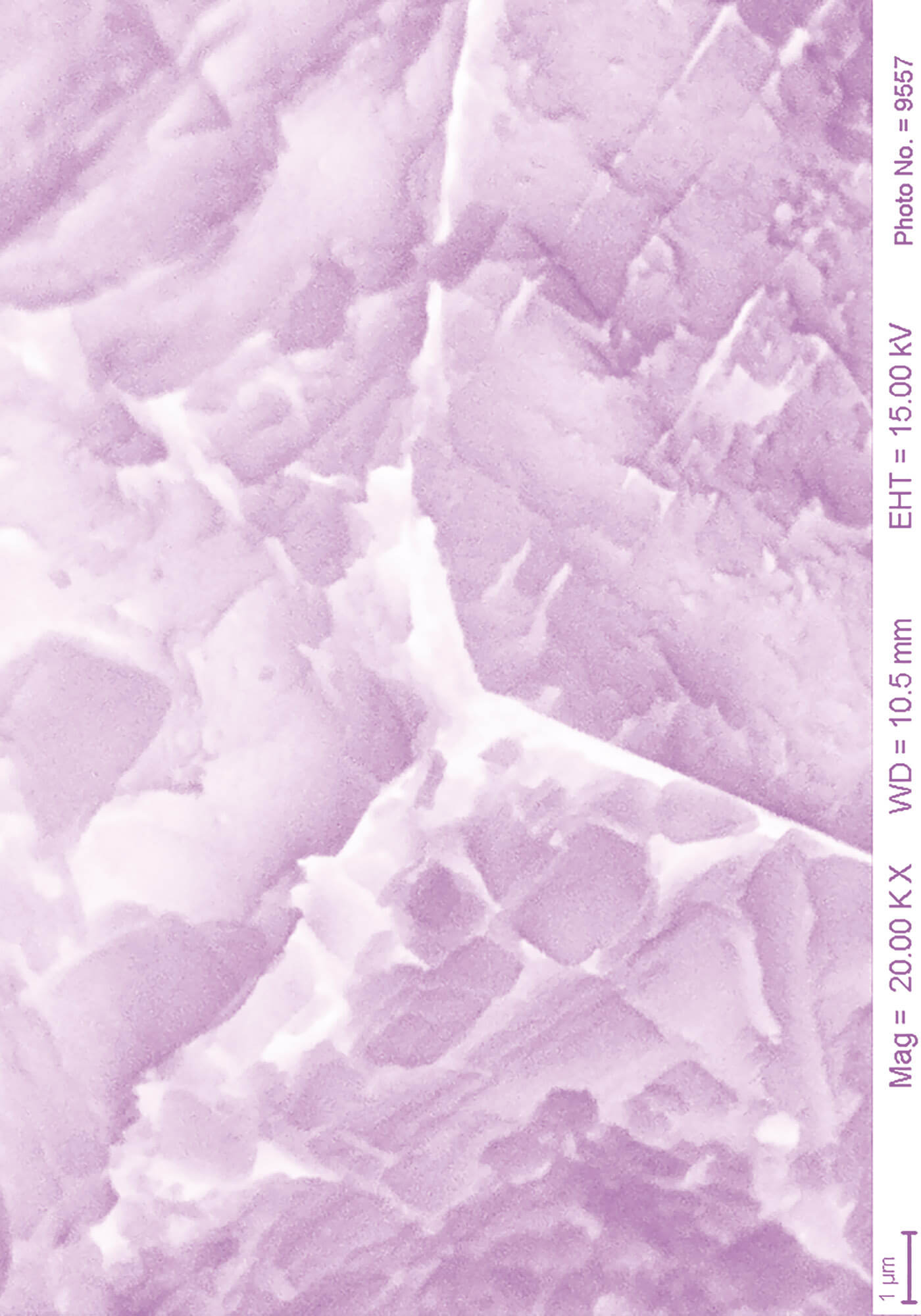

This work by Caterina Morigi explores the mineral dimension at micro and macro levels as an

element of contact between the natural world and the human body, starting from the observation

that just as human bones are made up of calcium phosphate so mountains are geological formations

of minerals, especially calcium carbonate, the main compound of marble.

In recent years, the artist has collaborated with a number of architectural engineers and

researchers of the University of Bologna and Rizzoli Institute of Bologna, engaged on

discovering new ways for conserving this material. After establishing that human bones are the

body parts that survive the longest and that in particular environmental conditions the organic

or mineral part is the best preserved, scientists have analysed its microbiological functioning,

observing a series of characteristics that can be taken as an example for the innovation of

marble used in sites exposed to harsh weather.

Thanks to these analyses, scientists have developed a series of further studies that go in the

opposite direction. Starting from the shells, biocompatible materials that can be used for

making protheses or elements to insert into the human body are now in the design phase.

From this research and the observation that collaboration between the human world and the

natural one can also occur in the mineral sphere, Caterina Morigi has realised the work The

Common Skeleton of Things.

The superimposing of images of marble, bone, landscapes and microscopic details of the same raw

materials aims to reveal how the sphere of the human and what is other than human – in

this case

the mineral world – have much more in common at a substantial level than we had imagined, or,

indeeed, are fully miscible.

Caterina Morigi

The Common Skeleton of Things, 2024

Stampa diretta su plexiglass, con cornice in alluminio

Courtesy the artist and Studio G7 Gallery, Bologna

From Marble to Bone, From Bones to Marble

In nature, many of the non-living (i.e. stone) and living (such as seashells and bones)

materials are formed by mineralization processes, that can last millennia, or just a few

hours.

As a result of mineralization, many stones, such as marble and porous limestones are

formed, constituted entirely or in part, by one same material, i.e. calcium carbonate

(CaCO3). Calcium carbonate determines the characteristics of stones, but is also their

main element of weakness. Indeed, although stone is generally regarded as an “eternal”

material, in the reality it degrades progressively as a result of the interactions with

the environment (rain and sun heat), leading, through the centuries, to the loss of

millimeters or even centimeters of stone surfaces.

However, soluble calcium carbonate is somehow similar to the mineral that constitutes

our bones, hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)3OH2), which is insoluble and highly resistant. More

into details, calcium carbonate can be transformed into hydroxyapatite by simple

immersion in a saline solution, thus forming a protective layer on the surface of the

stone, protecting it from the aggressive environment and restoring its cohesion.

For this reason, in the past years, several treatments have been developed to transform

the surface of stone into hydroxyapatite, to protect it. When hydroxyapatite forms onto

stone, it shows a specific morphology, characterized by nanoscale flakes. However, on

site, the protective layer can change composition and shape, due to the presence on

contaminants in the stone, thus resulting in a flowery-like architecture, which is

fascinating, but scarcely protective. For this reason, each specific substrate shall be

studied separately, in the lab and on site.

Just like marble, seashells are also constituted by calcium carbonate, so they can also

be converted in hydroxyapatite, this time to obtain materials capable of regenerating

human bones. Indeed, host cells can progressively degrade and convert into bone any

material that resembles its composition, also called biomimetic materials. Upon

conversion into hydroxyapatite, seashells can be used to “trick” our bones, by creating

artificial bone substitutes that perfectly mimic bones composition and architecture (for

instance, by exploiting 3D printing). This triggers host bone, which recognize the

substitute as “self”, progressively dissolves and incorporates it, hence making it a

part of the human organism.

— Gabriela Graziani

Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering “Giulio Natta”, Polytechnic of Milan

Marzia MiglioraBio

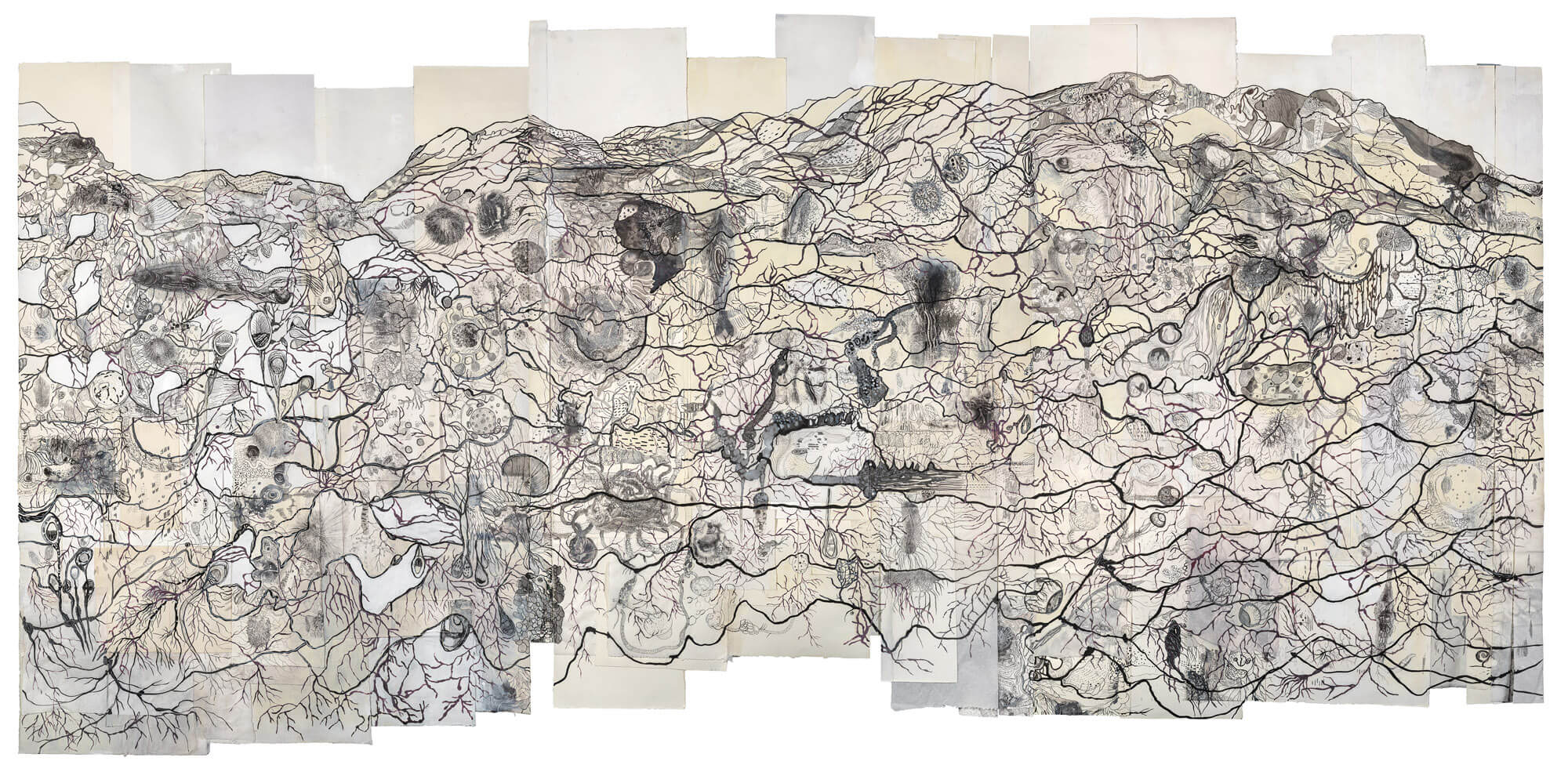

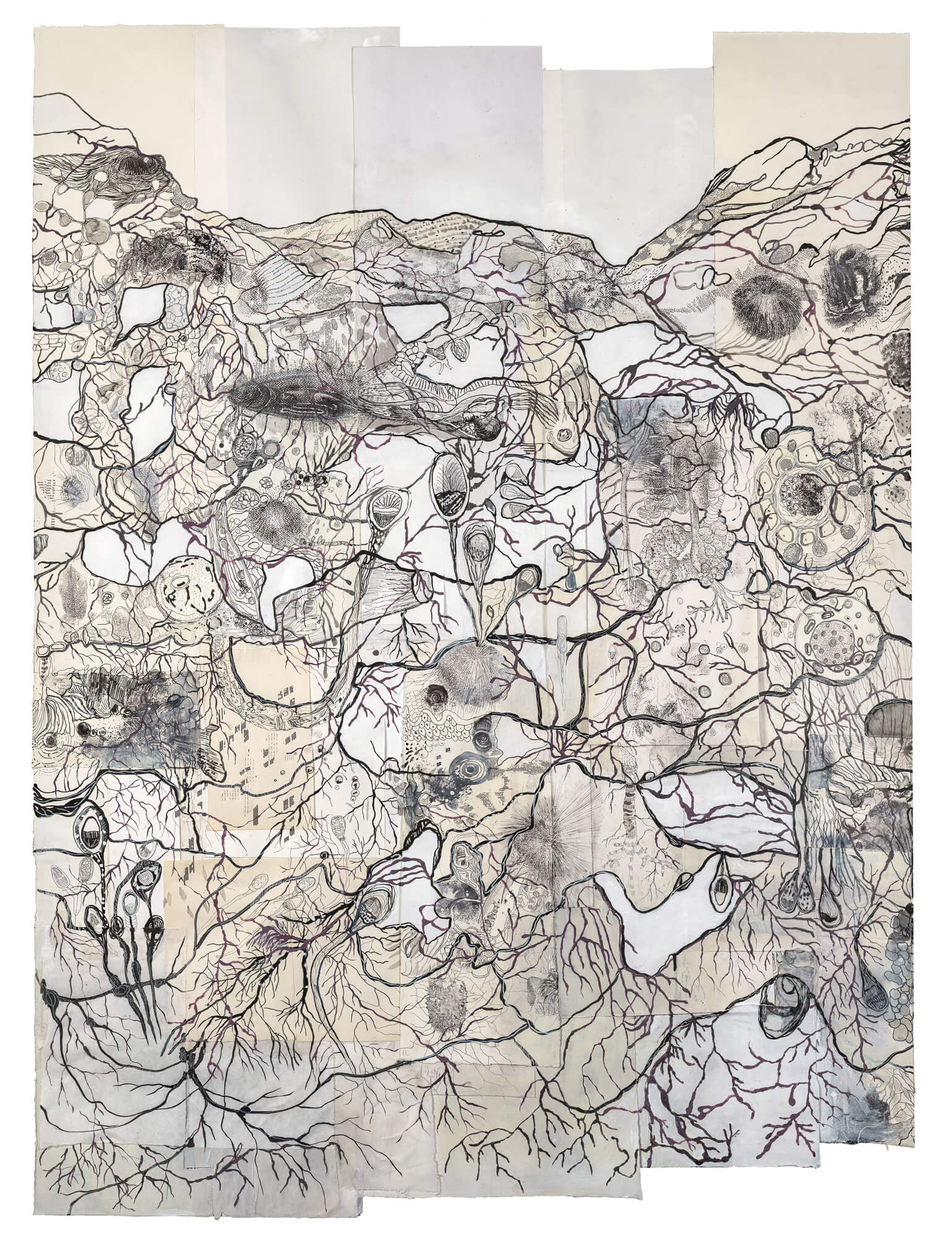

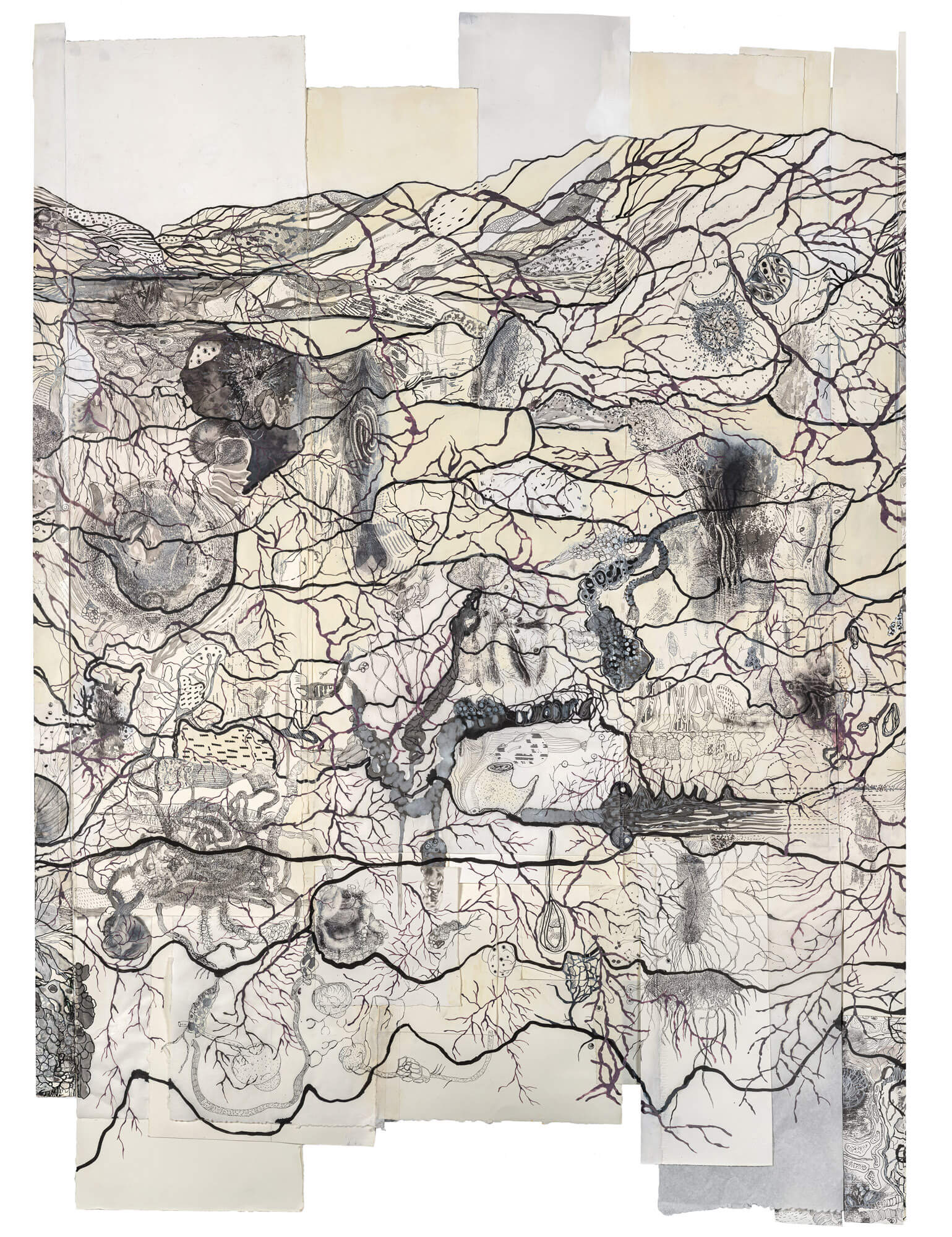

This work emerged from the dialogue with Massimo Bernardi, paleobiologist at MUSE and Alice

Labor, and was reaslied during the artist residency Arte a San Leonardo, in the Trentino winery

of the same name.

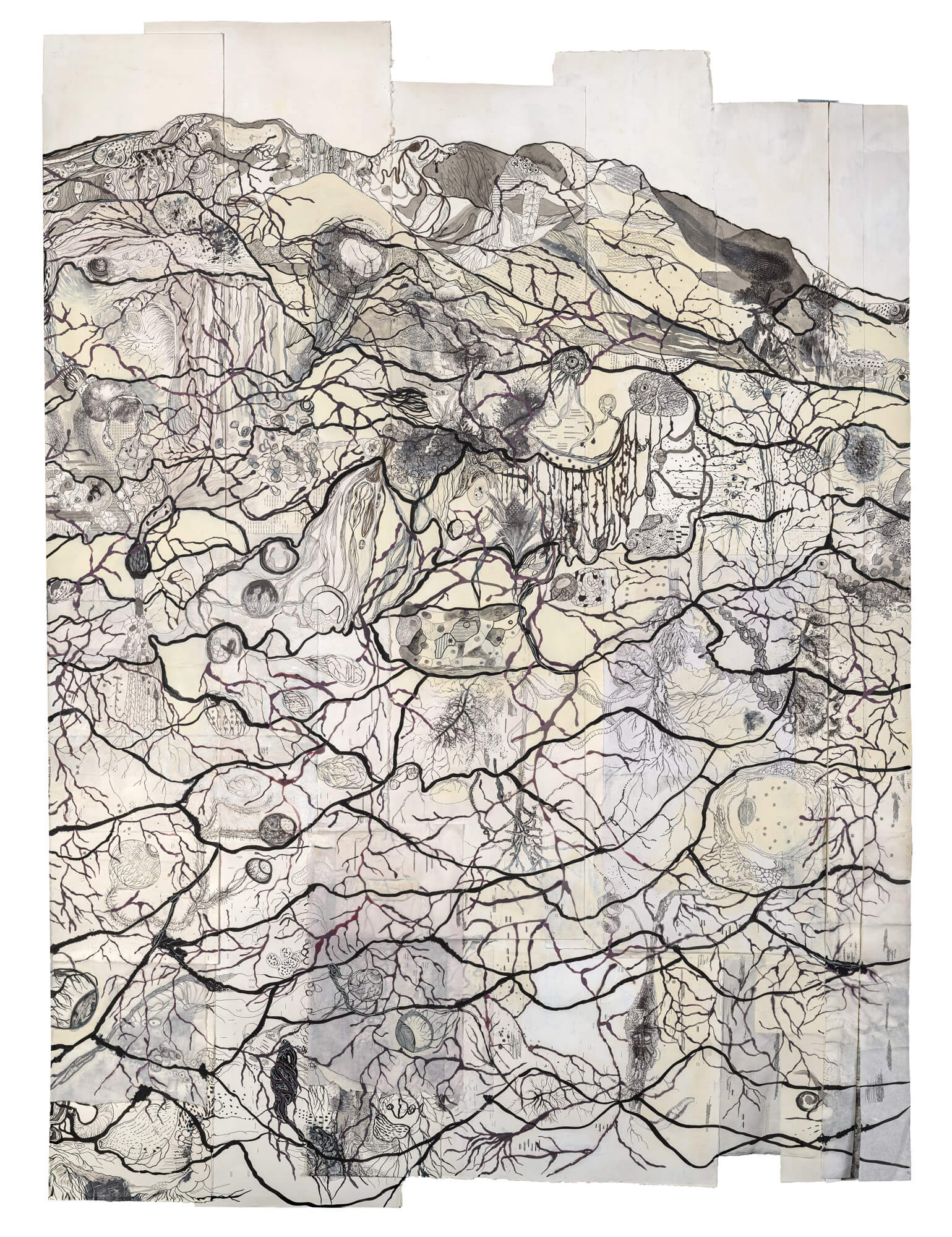

The outlines of Mount Baldo and Mount Lessini stand out in the triptych of drawings. A triumph

of marks and interweaving lines flourish in the line below the mountains that recall both the

circulatory system and the capillaries present in the human body, as well as the system of

rhizomes and roots that traverse a forest floor. Images from a number of human and animal

anatomy engravings can be found in this complex system of arabesques and biomorphic and

phytomorphic curves, which, for homomorphism, flow into each other, in a consant exchange of

meanings, symbols and visions.

Marzia Migliora attempts to narrate the voyage of a more-than-human element, tartaric acid, a

precipitate already present in grapes since flowering, that naturally crystallises at the first

cold temperatures on the edges of the wine maturation tanks, just when the colour and aromas of

the wine are stabilising.

Within this story, the tartaric acid becomes a bridge between the landscape and the human

body.

It narrates the constant cycle of this material, which begins in the rocks in the mountains, is

then stored in the grapes, and subsequently drunk, becoming part of us human beings. The

portrayed result is an image of a great multi-species, vital, pulsating organism that we are

part of. A primordial environment in which the lines of continuity and relationships inside and

outside the human and non-human body are evident and inevitably produce changes and adjustments

in our biological sphere.

Within a broader cycle of research – which has led Marzia Migliora in recent years to explore

the relationship between food production, commodities and surplus value of the capitalist model

and to the exploitation of human, animal and mineral resources – this work asserts the need to

re-think not only cultural, but also economic and productive, paradigms, and a rapprochement

with a biocentric and interspecies awareness.

Marzia Migliora

Paradossi dell'abbondanza #61 (La rivoluzione del tempo profondo),

2024

Drawing, transfers, tartar dust embossed on paper, three panels

Private collection. Produced on the occasion of Arte a San Leonardo

Courtesy the artist and Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan/Naples

The Spider Web of Life

Every plant product that we find in various forms and recipes on our tables absorbs and

re-processes valuable substances offered by nature, synthesizing them according to their

specific primary or secondary metabolism: from water to minerals, from carbohydrates to

fats and proteins up to the secondary metabolites, among which vitamins, polyphenols,

anthrocyanins and carotenoids. These secondary metabolites, or micro-nutrients, perform

vital functions both for plant health and for our organism, protecting us from oxidising

agents and reinforcing our immune defences. Tartaric acid is especially abundant in

grapes and tamarinds and is so representative that it has been adopted as a standard in

analysing the acidity of food liquids.1

That is not all: tartaric acid is an exceedingly interesting product of grape-pomace

extraction. Extraction techniques have varying degree of efficiency, depending on

temperature, acidity and calcium chloride levels: in any case, significant extraction

yields can be obtained, ranging from 50 and 75 grams of tartaric acid per kilogram of

pomace.2

Thanks to its antioxidant (acid regulator) and preservative properties, tartaric acid is

used widely in various food categories, including dairy products, edible oils and fats,

meat and fish-based products, fruit and vegetables, and non-alcoholic and alcoholic

drinks. In a modified form, tartaric acid is also used in bakery products, thanks to its

capacity to react with sodium bicarbonate to produce carbon dioxide without requiring

long, costly fermentation processes. This is why more research than ever is being

carried out on more sustainable, efficient and productive pomace extraction methods,

since a compound of special molecules hidden in the very hard seeds of the pressed

residue can also be relinquished: oligomeric proanthocyanidins. These count among the

most antioxidant molecules known in nature.3

From the rocks of the Baldo and Lessini Mountains in Italy, from the subsoil of

Mediterranean hills, or even from the rocks of high-altitude mountains, where grapes are

cultivated above 1000 metres, the tartaric acid path is long and complex: a spider web

of life that from the inert depths of the Earth envelopes every moment of our existence.

— Francesco Meneguzzo, Federica Zabini

Institute of BioEconomy, CNR - Sesto Fiorentino (FI) CAI Central Scientific Committee

- C. Venkitasamy, L. Zhao, R. Zhang, Z. Pan, “In Integrated Processing Technologies for Food and Agricultural By-Products”. Elsevier Inc., 2019. LINK→

- G. R. Caponio, F. Minervini, G. Tamma, G. Gambacorta, M. De Angelis, “Promising Application of Grape Pomace and Its Agri-Food Valorization: Source of Bioactive Molecules with Beneficial Effects”, Sustainability, 15 (11), 2023. LINK→

- F. Nie, L. Liu, J. Cui, Y. Zhao, D. Zhang, D. Zhou, J. Wu, B. Li, T. Wang, M. Li, M. Yan, “Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins: An Updated Review of Their Natural Sources, Synthesis, and Potentials”, Antioxidants, 12 (5), 2023. LINK→